By Bernie Clark, September 28th, 2020

Rethinking Plastic versus Elastic

In Yin Yoga we target the yin tissues of the body. But what are these yin tissues? One often-used metaphor is that yin tissues are the more plastic tissues like our ligaments, while the yang tissues are the more elastic tissues like our muscles. But this analogy is incorrect in one important way: ligaments are actually more elastic than our muscles.

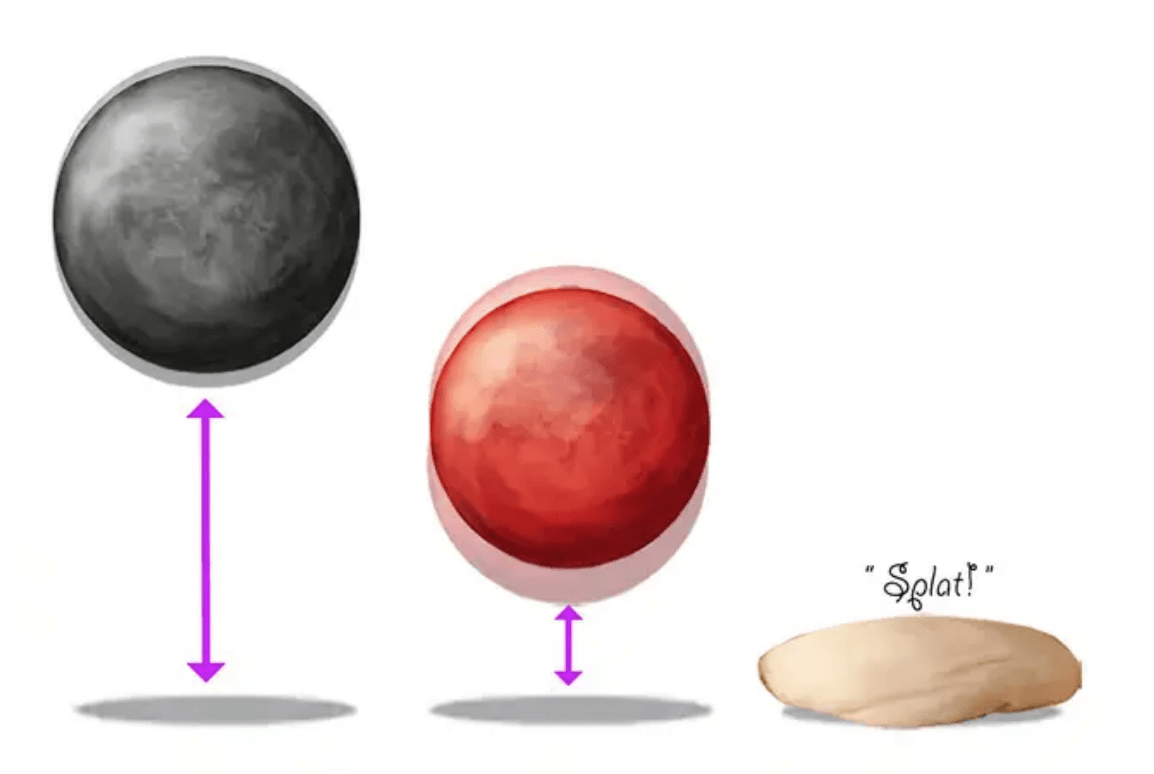

In his 2002 book, Yin Yoga: Outline of a Quiet Practice, Paul Grilley stated, “When we move and bend our joints doing Yoga postures, both muscles and connective tissues are being stretched. The muscles are Yang because they are soft and elastic, the connective tissues are Yin because they are stiff and inelastic.” This was my thinking for the last two decades as well, until I realized that by a strict engineering definition, this is not quite right. Elasticity is not related to stretchiness, but to how much energy is returned after a stretch ends. A more elastic material returns more of the energy used to elongate it when the stretch ends than does a less elastic material. A stiff spring is more elastic but less stretchy than a loose spring. In the same way, a steel ball will bounce higher off a concrete floor than a rubber ball dropped from the same height because the steel ball is actually more elastic than the rubber ball!

A steel ball certainly is not as stretchy as a rubber ball, but due to its higher elasticity, the energy used to deform a steel ball will be almost completely returned as the ball resumes its original shape. More of the energy of deformation of a rubber ball as it bounces is lost as heat, which prevents the rubber ball from bouncing as high as the steel ball. In the same way, our ligaments are more elastic than our muscles. They are the stiff springs of our body.

Something that is plastic will remain deformed after it has been stretched, like a ball of dough dropped on the floor. The ball of dough will not rebound to its original state. If we overstretch our ligaments, they too become plastic and will no longer return to their original state. However, this does not mean that ligaments are always plastic. Even muscles that have been overstretched will remain longer or plastic. Overstretching any tissue damages it and makes it plastic. We are not advocating overstretching tissues. Both muscles and ligaments are elastic to some degree but they become plastic if damaged by overstretching. So, the term plastic applied solely to our fascia, ligaments, etc. is incorrect.

Stiff versus Compliant

For a long time, I confused elongation with elasticity. This was incorrect. Our muscles can stretch longer than most ligaments, but they are not more elastic than the ligaments; they are more compliant than the ligaments. A ligament when stretched will snap back with more force (like the steel ball bouncing) than will a stretched muscle (more like the rubber ball). Indeed, a muscle doesn’t “bounce back” at all when it shortens. A muscle has to actively contract, using up energy, to regain its unstretched length. A ligament, like a spring, elastically recoils without any extra energy needed to return to its original length.

These are two terms we should get used to: stiff and compliant. A stiff material does not elongate very easily, whereas a compliant material will stretch with little effort. Our muscles are more compliant (yang) than our ligaments (yin). Said another way, ligaments are generally stiffer (yin) than our muscles (yang). We do not need to invoke the terms elastic or plastic at all. Our yin tissues are stiff relative to our yang tissues, which are compliant.[i]

As Paul points out in his teachings, the terms “yin” and “yang” are relative adjectives. Nothing is absolutely yin or yang. These terms can only be used contextually. Hot water is not yin or yang. Relative to boiling water, hot water is yin. Relative to ice, hot water is yang. Consider a cup of coffee: is it yin or yang? It depends on the context! The blackness of the coffee is yin but its heat is yang.

Context is key

So, are connective tissues yin or yang? The case can be made either way, depending upon the context. Bones are dry; yang is dry. So are bones yang tissues? If the context is the amount of water, then—yes, relative to muscles (80%–95% water), bones are yang. If the context is stiffness, however, bones are stiff (yin) and muscles are compliant (yang).

There are many components of connective tissues or fascia. The collagen fibers, which mostly make up ligaments, tendons and joint capsules, are dry (yang) but stiffer (yin) than muscle cells. However, some connective tissues have a lot of elastin fibers, which makes them stretchy (yang). Some fascia has lots of water (yin), but other fascia is very dry (yang).

In another context, muscles are active tissues: we can deliberately engage/contract them (that’s yang). Fascia, by contrast, is passive tissue: we can’t consciously contract it (which makes it yin in this context).

I think it is okay to generalize and say that tissues like ligaments, tendons and joint capsules are yin-like compared to muscles (and thus respond better to yin-like stresses: long-held static loads), but always is always wrong (and never is never right). Generalizations do not always hold true. There are some ligaments that are very yang-like in terms of elasticity (the ligamentum flavum), but they are still passive tissues, which is yin-like relative to active tissues.

Yin and Yang: Passive and Active

I believe, ultimately, that the context of passivity and activity is the best metaphor for deciding when to do yin or yang exercises, but of course there could be other contexts applied as well. Perhaps we should drop the elastic or plastic dichotomy in favor of compliant or stiff. But, even better, let’s think of our yin tissues as being more passive and our yang tissues as more active. Yin Yoga is a passive practice: we allow the stress to soak into the tissues. Yang forms of yoga are more active: we move and engage the muscles in order to remain briefly in a posture.

[i] For a more in-depth dive into this discussion, please read my article in Yoga International: It’s Okay to Stretch Your Ligaments.