Adapted from Your Upper Body, Your Yoga

By Bernie Clark

Updated June 24, 2024

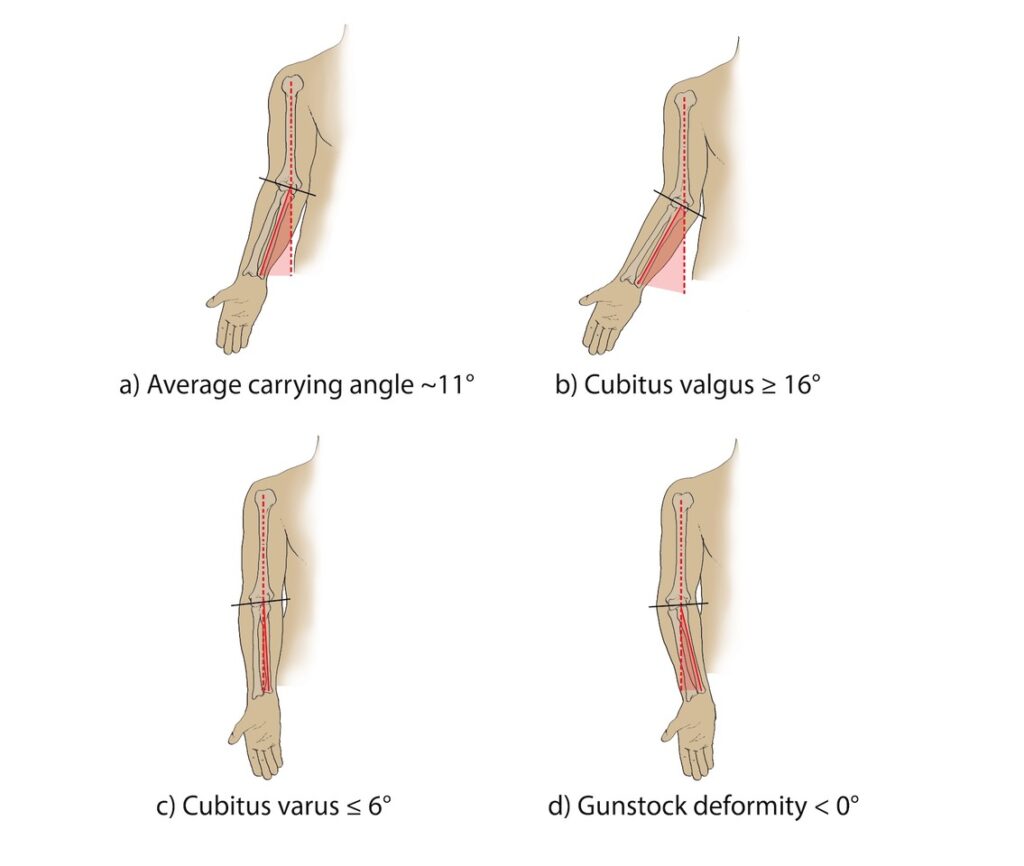

When we stand with our arms at our sides, palms facing forward, there is a distinct angle formed between our upper arms and our forearms. This is called the carrying angle (see figures 1 and 2). Many yoga teachers and their students have definite ideas of the proper distance between the hands in postures where the hands are on the floor, such as in Down Dog or Handstand. Unfortunately, not all these dogmatic teachers agree on what this proper distance should be, but often the catch-all direction is “hands shoulder-width apart”. That may work well for these teachers and most of their students, but due to variations in the carrying angle, for many students, this one-size-fits-all prescription does not work well.

Why the forearm is angled away from the line of the shaft of the humerus is not known, but there has been speculation that pointing the forearm away from the pelvis makes it easier to carry objects (thus the term “carrying angle”) and to swing the arms past the pelvis when walking or running. If the carrying angle is five degrees more than average, the condition is called cubitus valgus. If it is five degrees less than average, it is termed cubitus varus. If the forearm is so highly varus that it points in toward the body, it acquires a special name: a gunstock deformity (see figure 2d).1

What is the average carrying angle? Studies vary considerably, but almost all studies have found that our carrying angle increases throughout adolescence, so adults have a greater carrying angle than children. Usually, the dominant arm has more angle than the non-dominant arm. Women tend to have larger angles than men. The speculation is that women have broader hips than men, on average, so they need a larger carrying angle to keep the hands further away from the pelvis. However, the range of human variation is such that many women have small carrying angles and many men have large ones. Plus, it seems that shorter people have larger carrying angles than taller people, so the variation between men and women may be due more to variation in average height than specifically to gender.

One study of over a thousand people found the average carrying angle for the dominant arm was 11.25° and for the non-dominant arm was 10.6°.2 (This does not seem to be a very significant difference, but these are average values, and you may have a considerable difference between your two sides.) For some reason, left-handed people tend to have slightly higher carrying angles than right-handed people, regardless of the arm. Women average about 1.5° to 3.3° more than men.3 People over 14 years of age average about 1° more than children under 14 years of age.4

The terms cubitus valgus and cubitus varus imply a pathology or problem, yet being diagnosed with a valgus or varus elbow is not necessarily a big deal. The standard deviation for the carrying angle is around 4°, which means a normal distribution of carrying angle ranges from 3° to 19°. In other words, you could have a carrying angle of 19° and still be considered “normal” and not suffer any functional impairment!

But forget the statistics: what is important is your carrying angle. The absolute range of carrying angle in the study of over 1,000 people ranged from zero to 23°. An important question is what your angle means for you and your yoga practice.

Your carrying angle will affect your hand positions

Your carrying angle can affect the position of your hands and shoulders during your yoga practice. To understand this, first determine your carrying angle. Stand in front of a mirror with your arms at your side and your palms facing the mirror. Keep your elbows in so they hug your torso. Notice how much your forearms angle out to the side relative to your upper arm, which should hang pretty much straight down. Holding a straight stick (like a yardstick, pointer or broomstick) along your upper arm may make the angle more apparent. Notice if there is any difference between your left and right sides.

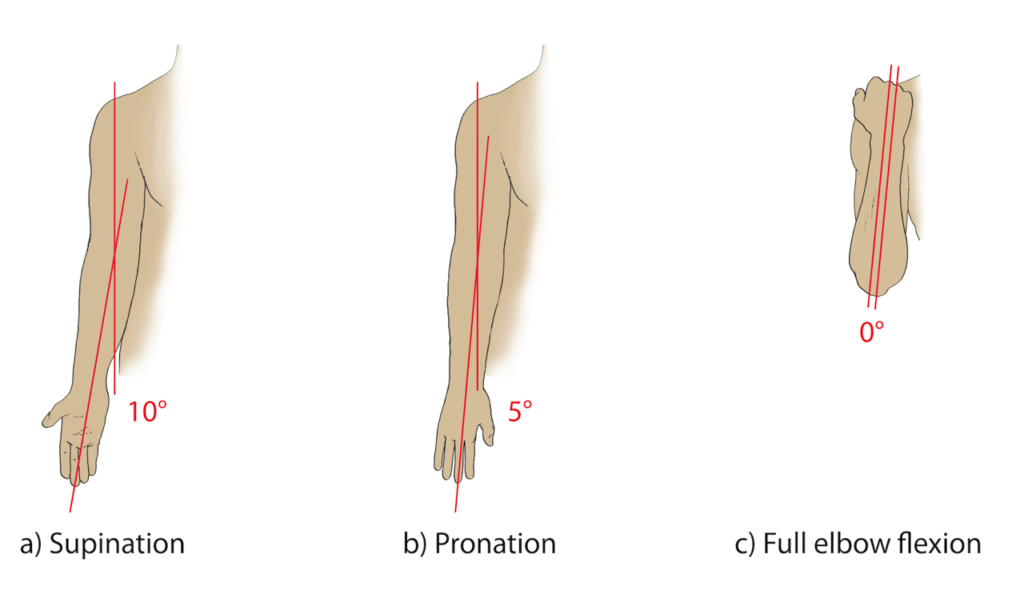

In this position with palms opened forward, your hands are fully supinated. There are very few yoga postures where the arms are straight with hands supinated and bearing weight. Usually, our hands are pronated fully, especially when they are on the floor. Still facing the mirror, notice what happens to your carrying angle as you slowly pronate your hands so that the palms face away from the mirror. As the wrists pronate, the carrying angle tends to diminish or even disappear! (See figure 3b.) The pronation of the wrists will reduce your carrying angle by 5–10°, depending upon the relative length of your forearm, the width of your wrist and how you pronate the forearm. (Normally, pronation will roll the radius over a stationary ulna, which will diminish the carrying angle. However, it is possible to move the ulna laterally during pronation so that the carrying angle does not change at all; the distal ends of the radius and ulna simply change places.5)

Interestingly, as the elbow flexes, the amount of carrying angle decreases. When the elbow is fully flexed, there is no angle at all between the forearm and the upper arm (see figure 3c). The hand is aligned with the shoulder. You can also try this in front of your mirror. Again, standing with palms open to the front, notice how the angle between the arm and forearm disappears as you bring your hand to your shoulder. At halfway, or 90° of flexion, your carrying angle is about half of its maximum. When we add the 5–10° of inward movement due to pronation, this may neutralize your carrying angle completely at the halfway point of full flexion. When do we flex the elbow 90°? In the lower push-up position (Chaturangadandasana), in forearm balancing postures like Feathered Peacock Pose (Pinchamayurasana) or in Sphinx/Low Cobra Pose (Bhujangasana). In these postures, with the elbows flexed 90°, the hands may be shoulder width apart and the shoulders may be neutral.

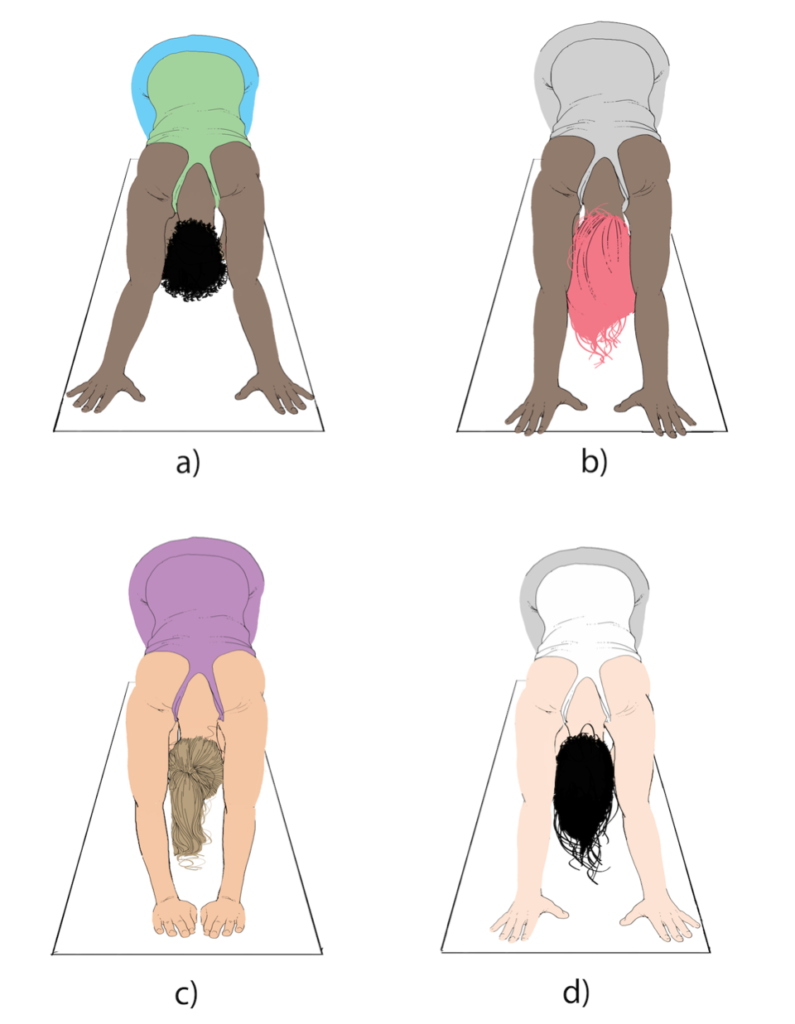

For many people, a pronated forearm aligns the hands with the shoulders, so when the hands are on the floor, having the hands shoulder width apart keeps the shoulder neutral in alignment. However, that is not the case for everyone. If you raise your arms overhead via flexion of the arms straight forward and external rotation at the shoulders and if your carrying angle is much larger than 10°, pronation will not bring your hands to shoulder width apart. The greater your carrying angle, the further apart your hands will be if the shoulders are to remain neutrally aligned. Figure 4 shows the effect of different carrying angles on hand position for Down Dog when the arms have been elevated and externally rotated. Notice that in each case, the shoulder and elbow positions have not changed; the distance between the hands changes due to the varying amount of carrying angle each student has. For a student who has a lot of carrying angle, with neutral shoulders the hands will naturally be wider than shoulder width (see figure 4a). For her to draw her hands to shoulder width apart will require some abduction of the arms, which will require more scapular movement. If someone has very little carrying angle, or even a varus angle, her hands may be less than shoulder width apart (the student in figure 4c). For this person, keeping the hands shoulder width apart will require more adduction of the arms at the shoulders.

One last time, stand in front of the mirror and compare your two sides. It is possible that you have a lot of carrying angle in one elbow but very little in the other. This asymmetry may dictate that your hands should not be symmetrically placed on the floor. Your Down Dog may have one hand wider to the side, the other more in line with that shoulder. This is case for the student in figure 4.d.

What works ideally for you will have to be determined through experimenting with your hand positions and finding the place for them that keeps each shoulder as neutral, “uncontorted” and comfortable as possible.

Footnotes:

_________________________

1 In a gunstock deformity, the upper arm represents the stock of the gun or rifle, while the forearm represents the barrel of the gun, which is angled inward with respect to the gunstock. This is an excessive cubitus varus. It is often the result of an elbow fracture that healed with the bones misaligned.

2 See E. Yilmaz et al., “Variation of Carrying Angle with Age, Sex, and Special Reference to Side,” Orthopedics 28.11 (2005): 1360–3. But that is an average. Personally, my right arm (the dominant side) is 15°, while my left arm (non-dominant side) is zero! Plus, other studies do not support this finding. See A.K. Açıkgöz, R.S. Balci, P. Göker, and M.G. Bozkir, “Evaluation of the Elbow Carrying Angle in Healthy Individuals,” International Journal of Morphology 36.1 (2018): 135–9.

3 The amount varies between studies. The difference of 1.5° is from Yilmaz et al., while 3.3° was from G. Paraskevas et al., “Study of the Carrying Angle of the Human Elbow Joint in Full Extension: A Morphometric Analysis,” Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 26 (2004): 19–23, doi:10.1007/s00276- 003-0185-z.

4 See Yilmaz et al.

5 For a deeper discussion on how we pronated our forearms, read pages 172-173 in Your Upper Body, Your Yoga.