Proportions in Yoga

Excerpted from Your Upper Body, Your Yoga

By Bernie Clark

February 16, 2024

There is a strong mythos in yoga that every body can do every pose if that body works hard enough, long enough, with the right guru, diet, supplements, scented candles and, of course, matching yoga outfit and mat. This mythos is patently false and ill informed. Everybody, and every body, is unique. One of the simplest and clearest examples of your uniqueness is the proportions of your body’s parts. There are many reasons why one yoga student can perform the Ashtanga jump through to sitting with grace and straight legs, while another equally experienced and motivated student continually crashes her butt into the floor with each attempt. The cause of her failure has nothing to do with her dedication, effort, will power, abhyasa or vairagya1 and everything to do with the simple fact that her arms are too short relative to the length of her torso.2 She does not possess the proportions necessary to excel in this particular movement. She is not alone.

Athletes choose their favored sport partly because their body’s proportions predispose them to excellence in that sport.3 Pentathletes tend to be tall, while weightlifters tend to be shorter and bulkier; female gymnasts tend to be shorter and slender, while rowers tend to be tall with broad shoulders. You will never find a 5’ tall gymnast excelling at professional basketball, while a 6’6” man will never be a prima ballerina. The size and proportions of your body will allow you to do very well with certain movements and will cause you to perform very poorly at others.

VARIATIONS IN PROPORTIONS BY OUR ANCESTORS’ GEOGRAPHY

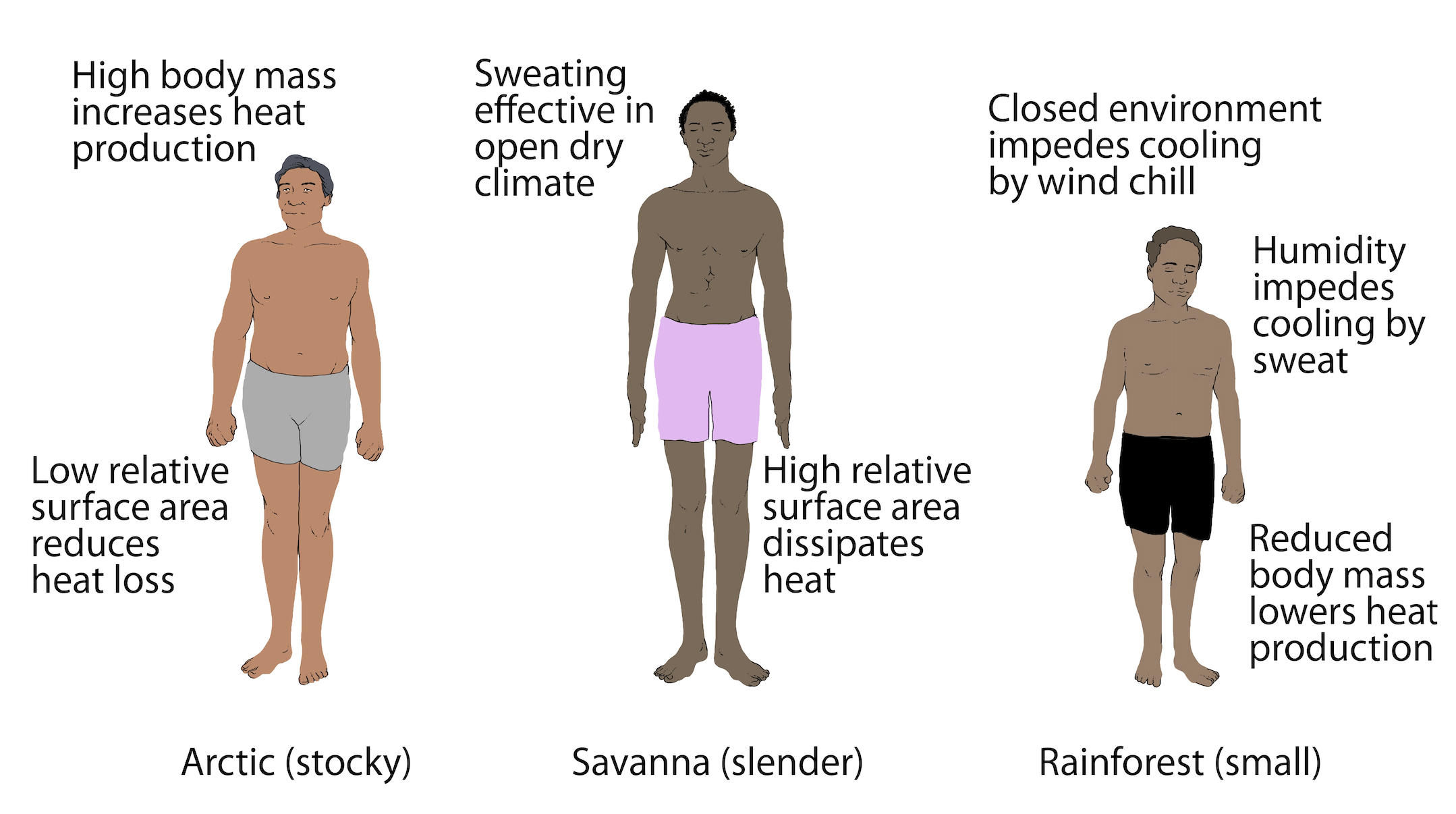

Animals have been observed to adapt to geographic conditions by changing their body’s proportions, and humans are no exceptions, as shown in figure 2. Carl Bergmann described this trend in 1847, although he was not the first to notice it. He found that bodies tend to be larger where it is cold, and smaller where it is warm.4 This is a genetically driven adaptation, and you will not suddenly grow a bigger body just because you moved to Alaska. Joel Allen stated in 1877 that animals in colder climates tend to have shorter limbs and appendages as well as wider pelvises and more body mass than those living in warmer regions. This is again an adaptation to the climate: shorter limbs lose less heat than longer limbs; longer limbs cool off more quickly than shorter limbs.5 This is correlated to not only latitude but also altitude. The higher you go, the colder the climate.

Like animals, people tend to follow Bergmann’s rule and Allen’s rule—although there are always exceptions! Indigenous Peruvians living high in the mountains tend to have shorter limbs relative to the torso than indigenous Peruvians living in the lowlands.6 The largest average body masses are found in the indigenous inhabitants of Siberia, who tend to have thick, short limbs. The smallest body masses are found in the tropical regions, even though tropical inhabitants tend to have longer limbs. In general, people with European heritage have body proportions more similar to the Inuit than to the sub-Saharan bodies of tropical Africa.7

Of course, humans are complicated, and climate is but one factor determining body size and proportions. An individual’s body is affected by nutrition, social standing, life history and the ecology of their surroundings.8 Exceptions to any norm are numerous,9 and that is the point: humans are variable. There is no one predetermined proportion that perfectly describes the human form. All we can say is that proportions vary widely for lots of reasons. There is no Vitruvian ideal for the perfectly proportioned person. The important questions are: What are the consequences of your proportions? What can you do easily, and what will always be a challenge for you?

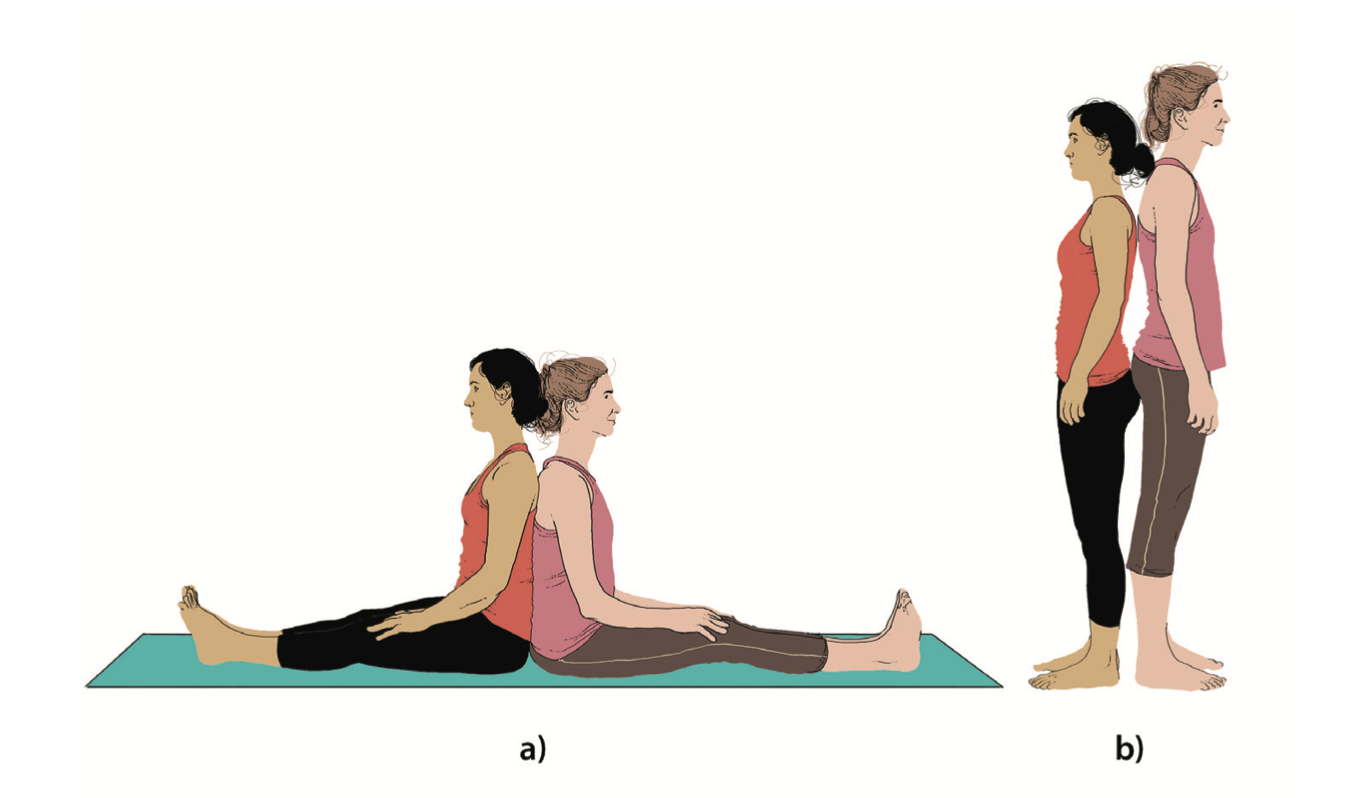

Torso to legs proportions (the Cormic index)

The students drawn in figure 3 are based on real people.10 On the left is Leslie, and on the right is Emilie.11 They are perfect illustrations of the variations in the ratio of sitting height to overall height, called the Cormic index (CI), and how our CI affects our yoga postures. As shown in (a), Leslie has a larger sitting height than Emilie, but as shown in (b) when they both stand up, Emilie is taller. Leslie has a Cormic index about 10% higher than Emilie, which means that Leslie has a longer torso relative to her legs than Emilie. The average person has a Cormic index of 51%, but as these two women demonstrate, not everyone is average. The relative length of your legs to your torso will affect how easily you can do certain postures, or how challenging they may be.

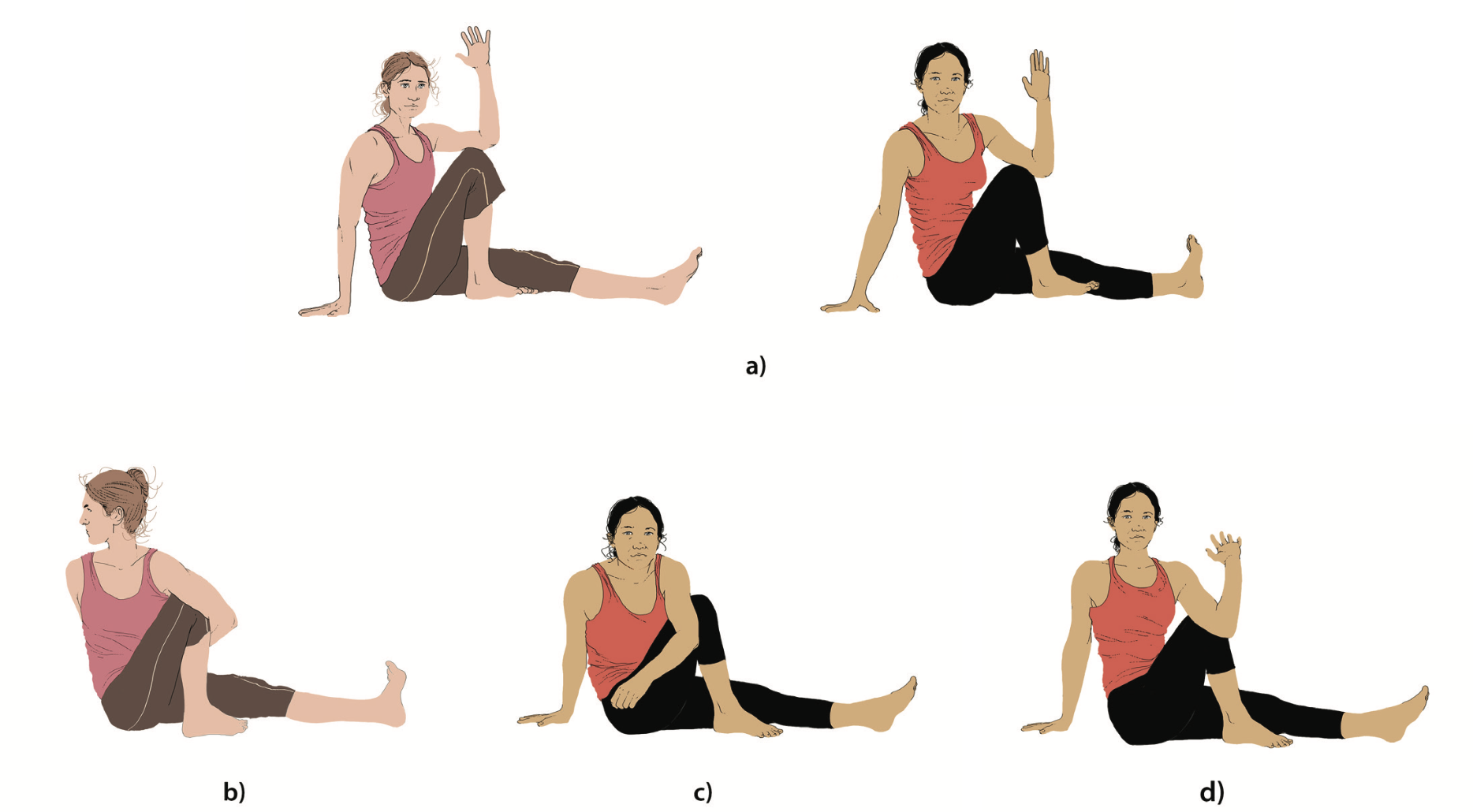

In figure 4.a, we see what happens when Leslie and Emilie prepare for two seated twists (Ardhamatsyendrasana and Marichyasana C). Notice how the top of Emilie’s knee is much higher than Leslie’s. When Leslie brings her arm to her thigh, she must lower the arm considerably more than Emilie does. Emilie can keep her spine relatively straight and wrap her arm around her leg because her elbow reaches well past her knee, providing her room to flex the elbow and internally rotate the arm. She is able to easily bind in this twist. However, as shown in (c), if Leslie wants to use her leg as a lever against which she can rotate her chest enough to either hold her straight leg or bind her arms behind her, she has to flex her torso to bring the shoulder down to the level of the leg. If Leslie remains sitting up straight, her elbow will be beside her knee, and she will be unable to internally rotate that arm, bend her elbow and bring that hand behind the leg. But that is okay—it is perfectly appropriate for Leslie to do her twist without binding the hands behind her back. Her spine can rotate just as much as Emilie’s, even though aesthetically it looks like Emilie is doing a much deeper twist. Certainly, Emilie is obtaining more stress in the left shoulder through the strong internal rotation of the arm than Leslie is getting. But there are other poses that Leslie can do to target her shoulder in that way, such as Cow Face Pose (Gomukhasana).

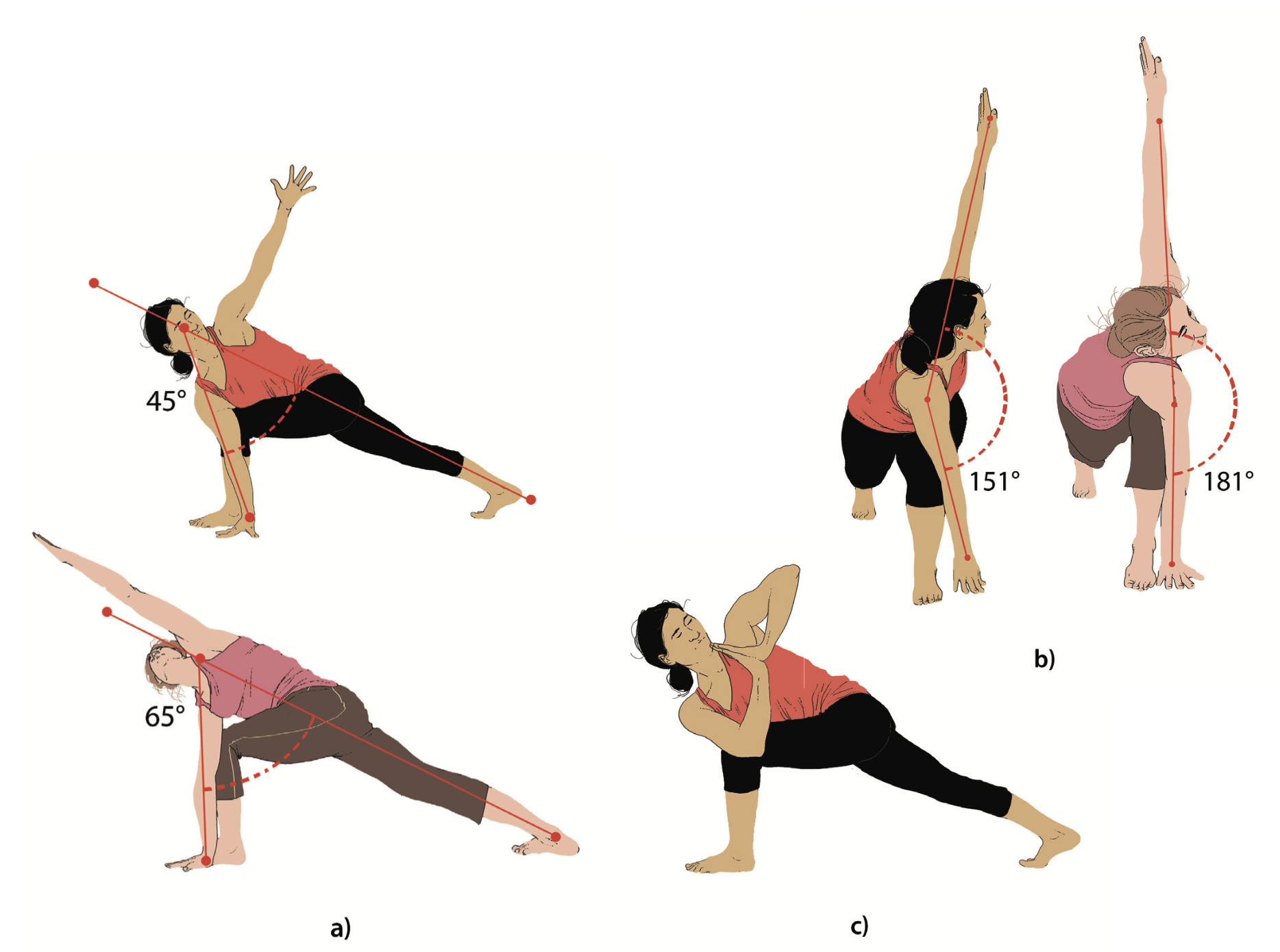

Another posture where the Cormic index affects yoga students is the Revolved Side Angle Pose (Parivrttaparsvakonasana). Notice in figure 5 how the CI affects the way this pose is done by Leslie and Emilie. With her longer thigh, Emilie can bring her right arm straight down to the floor outside the shin. Leslie, however, with a shorter thigh, must reach her arm backward to press it against her shin. As shown in (b), pressing the arm against the shin gives more leverage for the twisting aspect of this pose, which allows Emilie to get her chest outside the front leg. Since Leslie has to reach her arm backward, she does not have the same leverage available to pull her chest over the thigh. She must flex her torso to get her hand to the floor while keeping her arm against the leg. If she wants to keep her spine neutral, like Emilie does, Leslie can do the Prayer Hands version of the pose, as shown in (c), which allows her to bring her lower elbow outside the thigh to provide at least some leverage.

The optimal positions of our hands, arms, legs and feet are affected by the combination of upper body limb length and torso length relative to the lower body limb length. These relative proportions will affect the aesthetics of postures such as Down Dog (Adhomukhasvanasana), Half Moon Pose (Ardhachandrasana) and Triangle Pose (Trikonasana) and the locations and amounts of stress that occur.

TEST YOURSELF

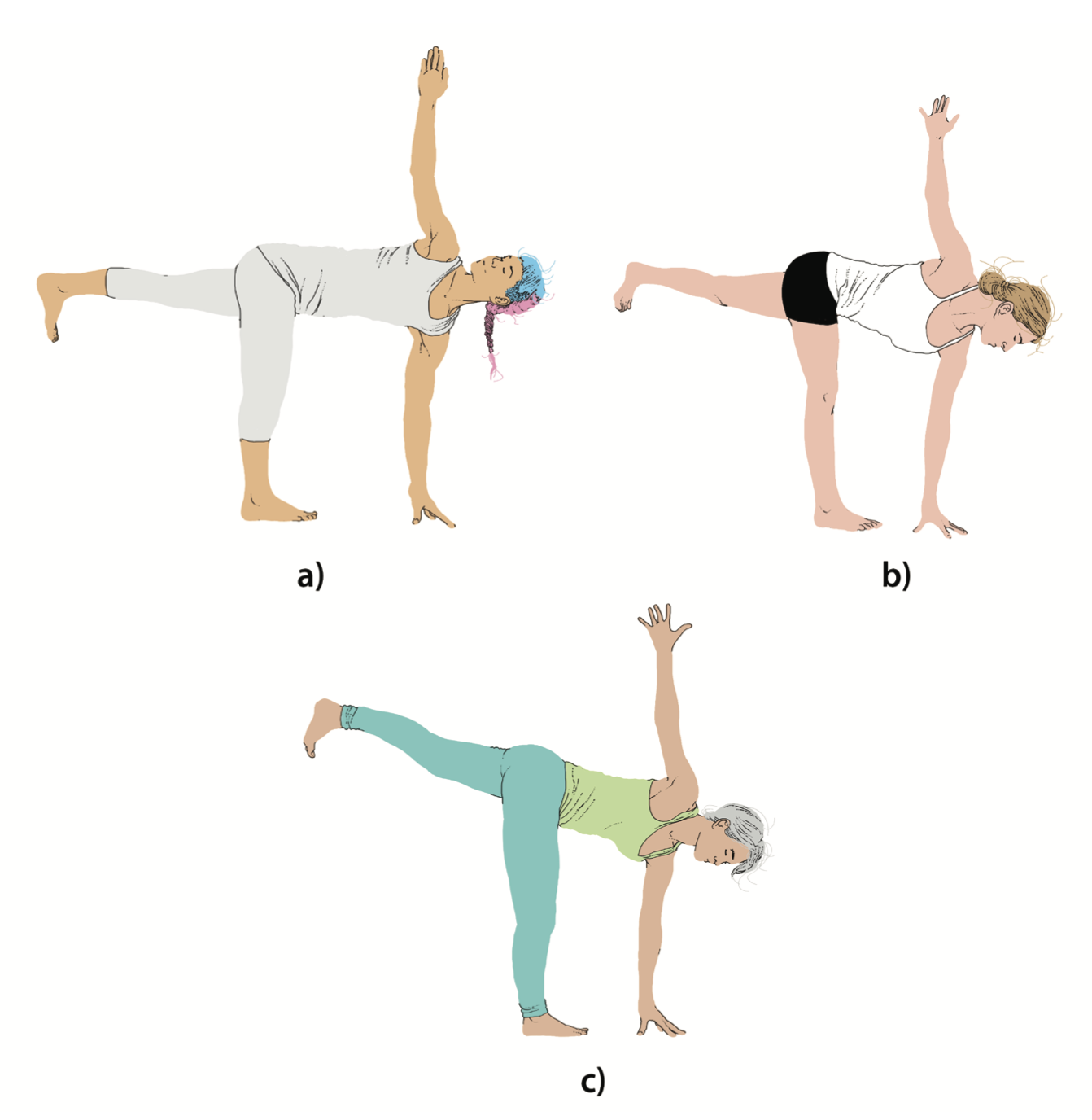

In the book, Your Upper Body, Your Yoga, there are dozens of examples of variations in proportions and their effect on yoga postures. As there is not enough space in one article to describe them all, the curious student may want to study the volume on proportions. But, for a final example of varying body proportions, examine the three students performing Revolved Half Moon Pose (Parivrttaardhachandrasana) in figure 6. These drawings are based on photographs of real students. Can you tell why they look different? Here is a hint: focus on the relative lengths of the arms, legs and torso.12

There are many ways we can compare body segment sizes and lengths. For example, we can compare our sitting height to our standing height: the Cormic index. Embedded within the Cormic index is the relationship of the length of our lower body to our upper body. Some people have long legs compared to their torsos, while others have shorter legs. Folding forward to touch the floor is easier for people with shorter legs. We can compare the length of our arms to the length of our torso. People with longer arms will also find it easy to touch their feet during forward flexions and to lift their torso off the floor in various seated postures. We can compare the length of our arms to our overall body height (sometimes called the ape index). Aligning our hands over our spread-apart feet will require more or less abduction of the legs, depending upon how wide your arm span is. Finally, within the limbs we can compare the distal segment to the proximal segment (called the intra-limb ratio). Long shins relative to arm length make it more challenging to bring the hand to the floor in lunges.

Certain proportions make certain movements easier, and other proportions make those movements more difficult. At the very least, people with one set of proportions will look different from those with another set. This is not a problem to be fixed, but it can be noticed and accommodated (perhaps through the judicious use of a block). Since variety in proportions is the rule, not the exception, it will serve both yoga students and yoga teachers well to remember why they are doing yoga postures. The point of any pose is not to look a particular way. Sure, a pleasing aesthetic appearance can be appreciated and even beautiful, but asymmetry and different proportions can also be beautiful in their own way. The point of a pose is to create an appropriate stress in a targeted area. As long as this is being achieved, the pose is proper, regardless of the student’s appearance.

_______________________

1 Abhyasa and vairagya are perseverance and detachment. They are cited in the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali (1.12) as the prerequisites of a successful yoga practice.

2 In other words, she has a short “ape index” which is a bit of sports jargon used for the ratio of arm span to height. One way to calculate ape index is to subtract your height from your arm span. The result is measured in either inches or centimeters. For most purposes the ratio can be expressed as a dimensionless number or as a percentage.

3 See L.L. Lauchbach and J.T. McConville, “The Relationship of Strength to Body Size and Typology,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 1.4 (1969): 189–94.

4 This is due to a well-known law of cubes and squares: a body that is twice as big in all three dimensions has eight times the volume as a body that is half the size. But the surface area of the larger animal is only four times bigger than the smaller animal’s, which means the larger body is able to maintain its inner temperature longer than the smaller animal. This is good for surviving in cold climates but not so good in warm climates.

5 See Christopher Ruff, “Variation in Human Body Size and Shape,” Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (2002): 211–32.

6 See Karen J. Weinstein, “Body Proportions in Ancient Andeans from High and Low Altitudes,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 128.3 (2005): 569–85, doi:10.1002/ ajpa.20137.

7 See T.W. Holliday and C.E. Hilton, “Body Proportions of Circumpolar Peoples as Evidenced from Skeletal Data: Ipiutak and Tigara (Point Hope) versus Kodiak Island Inuit,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 142.2 (2010): 287– 302, doi:10.1002/ajpa.21226. For a refinement of Bergmann’s and Allen’s rules, see Kristen R.R. Savell, Benjamin M. Auerbach, and Charles C. Roseman, “Constraint, Natural Selection, and the Evolution of Human Body Form,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113.34 (2016): 9492–7, doi:10.1073/pnas.1603632113.

8 See W.A. Calder, III. Size, Function, and Life History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

9 Living side-by-side in the Democratic Republic of Congo are the Tutsi, who are among the tallest people in the world, and the Mbuti, who are among the shortest people in the world.

10 The drawings are based on photographs taken at a 16-day retreat conducted by Paul and Suzee Grilley at the Land of the Medicine Buddha, in California, September of 2013.

11 My thanks to Emilie Fabre and Leslie Anthony for posing for the photos that these drawings are based on.

12 In figure 6, student (a) has a very high Cormic index, which means she has short legs relative to her torso. Indeed, her torso is much longer than her legs. While her arms are not overly long, because her legs are so short, it is easy to get her hand to the ground while keeping her torso perfectly vertical. Student (b) has a lower Cormic index than student (a). You can see that her legs are much longer than her torso and she also has fairly long arms. But her arms are not as long as her legs, so she has to dip her torso below horizontal to get her hand to the ground. Student (c) has a low ape index, which means she has long legs and short arms. To get her hand to the ground, she has to dip her torso more below horizontal than the other two students. Curiously, she also has a shorter shin but a longer femur than student (b).