A discussion on the source of emotions

By Bernie Clark, June 25, 2022

The trigger was the teacher saying, “some students hold a lot of anger in their hips!” After class, over cups of chai, two students discuss the comment. Craig, a psychotherapist, declared the comment was unnecessarily flowery, grossly incorrect and unfortunately a common trope in the yoga and wellness industry. Beth, a professor of neurology, begged to differ. Let’s listen in to their chat…

Brain/body boundaries – a spectrum

Craig: The components of the body include muscles, fascia, nerves, organs and much more but emotions do not reside in any of these places, they are merely locations where emotions may be expressed or felt. When someone is experiencing an emotion, we may be able to see it in their facial expression or way they hold their body, but this does not mean that the body is holding the emotion. The body does not store emotions. An emotion is a neurological process that can trigger a physiological reaction. All emotions are in the brain.

Beth: Be specific. If emotions reside in the brain, tell me where.

Craig: Well you know: it begins with the amygdala. Way back in the 1930s it was shown that monkeys with an amygdala can feel fear, but monkeys without them were fearless.1

Beth: But, since then we have learned that many people without an amygdala can experience fear.2 So, the amygdala is not the “home” of fear. Instead an amygdala seems to be sometimes involved with emotions but not always. If your premise is that emotions are only neurological, you will have to do better than pointing to the amygdala. In fact, even pointing to the brain is suspect because, where does the brain begin and end? Which part of the brain are you referring to? Does the brain end at the brainstem? But, that is continuous with the spinal cord. And the nerves from the spinal cord are connected to the peripheral nerves. And the peripheral nerves are embedded in myelinated sheaths and fascial wrappers. Are all these included in your definition of the brain?

Craig: Sure, I admit that the amygdala is not the home for emotions but it is part of a process for creating an emotion. There are core systems in the brain which activate when emotions are felt. These are the homes for emotions, if we can call them that.

Beth: But, no! What you call a core system is too variable. The brain is degenerate, which means that many things can cause the same effect. A neurological correlate or a fingerprint for an emotion in one person will be very different for another. There are no singular emotional fingerprints in the brain!3

Plus, you didn’t answer my question: if your point is that emotions are made in the brain, you have to put a boundary between the brain and the rest of the body, but that boundary is simply a mental concept, not reality. Like in a rainbow, the color red merges into orange: there is no sharp dividing line. So too, the brain is intimately connected to the rest of the body. The nerve endings in my abdomen, where I feel butterflies before I give a lecture, are part of the brain but they are located in my belly.

Craig: I will grant you that we use a reductionist approach of conceptualizing the body into parts to help us understand it, but what you feel in your gut is the effect of the emotion, which was generated in your brain, not the other way around.

Beth: You just begged the question by implying my gut neurons are different from brain neurons because they are not in my brain. My point is that it is all brain: the brain is spread throughout the body. But, I don’t need to belabour this point because your major premise is backwards!

Somatic correlates of emotions

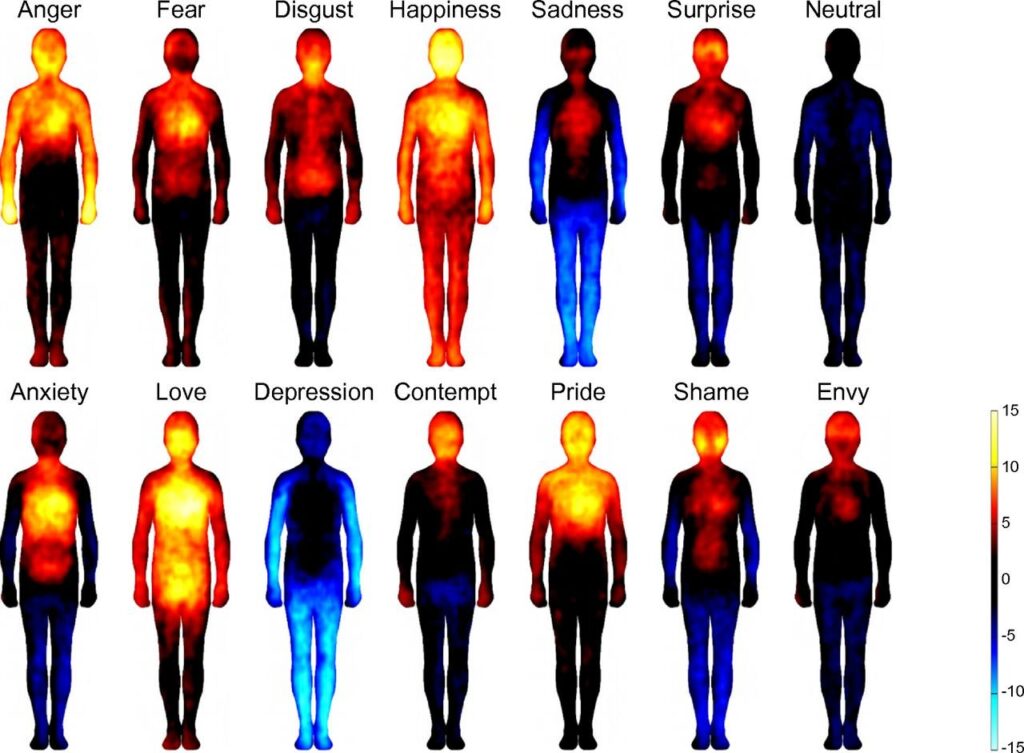

Beth: It is not the body that feels an emotion generated by the brain; it is the brain that senses the emotions that are generated in the body! Do you remember that study done in 2014 by researchers in Finland that showed a mapping of where people had sensations in their body when they experienced emotions?4 They compiled reports from over 700 participants and created maps of the locations of where people felt their emotions. The participants felt the emotions in their body not in their brains.

Craig: You accused me earlier of the logical fallacy of begging the question, but now you are committing the fallacy of confusing correlation with causation. Just because people felt something in their bodies does not mean that emotions are located there. I would agree that the body has certain physiological states when under stress, like a rapid heartbeat, more blood flow to the organs, sweaty palms, etc., and people can sense these changes. But, these physiological states are what give rise to the experience of emotion in the brain; they are not the emotions. The emotions are not in the body.

Beth: The difference between correlation and causation is important. Earlier you were implying that emotions are in the brain because we can detect neurological correlates to them there. This implies that if something is happening in the brain when an emotion is felt, then the stuff in the brain is causing it. That is also confusing correlation with causation. I am saying there are physiological correlates to emotions in the body as well as neurological correlates. So, if correlates imply the presence of emotions in the brain, then they are also in body as well because there are correlates there too. Regardless, no amount of correlation will explain the causation or the experience of an emotion.

Craig: Still, I stick to my point: just because you feel something in your body when an emotion arises, doesn’t mean the emotion is in your body. When the teacher said, “Anger is often stored in the hips,” that is just plainly wrong! Anger is generated in the brain and felt in the body because the brain causes physiological sensations.

Beth: I still think you have it backwards. The physiological state of the body is what causes the experience of emotion in the brain.

Predictive Processing

Beth: Look at our neighbour. She is eating strawberries. Look at that last one left. What color is it?

Craig: I think I know where you are going…it is clearly red.

Beth: Right, but – is that red in the strawberry? Is it real? Or is it all in your brain?

Craig: My experience of red is in my brain.

Beth: There are many models of consciousness that try to explain how the brain creates an experience. One of the latest models says that the brain predicts reality based on input from the senses. After all, the brain is just a glob of goo sitting in a bucket of bone with no direct connection to the outside world. It is receiving signals from our senses and it has to figure out what it all means. It does this by creating a simulation, a prediction if you will, and continually compares its prediction against new input. If there is a prediction error, a mismatch between its model and the data, it has to revise its simulation. It is the simulation that we experience, not the real world. It is suggested that the simulation is our experience! It is as if the brain is constantly creating controlled hallucinations. When the hallucination fits the input, all is well. If the inputs don’t match the hallucinations, the brain updates the simulation. If it doesn’t update the simulation, we have problems.

For the brain to experience that strawberry, light has to bounce off the strawberry, enter the eye, stimulate electrical activity that travels the optic nerve to the visual cortex which then sends signals to our memory centers, etc. Many parts of the brain are involved, as is the eye, before we experience the redness of a strawberry. Now, red is light of a specific wavelength. This light is not in the brain. You may say that the brain creates the experience of red, but you can’t say that red is not real. The photons of light entering the eye are real. The strawberry that is reflecting a specific wavelength of light is real.

Craig: Okay…granted.

Beth: Right, so much for the so-called “outer world”. We can experience it, the sense of experience is generated in our brains via predictions, but the outside world exists, otherwise no inputs would arrive at our sense organs. But there is also an “inner world”: our inner organs of perception allow the brain to continually track what is going on in our bodies. This is interoception, as you know. Some researchers propose that emotions are sensed via interception and these signals go to the brain, which creates a simulation of the body in the same way it creates a simulation of a strawberry. This simulation gives rise to the experience of emotion in the same way the prediction gives rise to the experience of the color red, but just as a red strawberry exists outside of the brain, so do emotions. Red is in the strawberry. Emotions are in the body.

Craig: I agree that light at various wavelengths, which we experience as colors, exist outside the brain and all we get is the experience of color, created by the brain. But, I don’t agree that there are separate emotions occurring in the body similar to light.

Beth: Well, something exists in the body, or else there would be nothing for the brain to be simulating! If you agree that the experience of emotion is a simulation, a prediction of the way the world works, in this case inside our body, then there must be a something in the body that the brain is sensing. This something is what the brain is basing its simulation on.

Analogy to pain

At this point, Craig leans back in his chair and Beth gazes into her now empty cup. After a short pause, Craig smiles and continues…

Craig: I am still not convinced. Think about pain as an analogy. Pain is created by the brain. It is not “in the body”. Now, before you object, let me clarify. The experience of pain is in the brain, but we both know that pain can have a physiologically trigger. But sometimes there is nothing physically wrong and yet pain can be present. This pain is totally created and experienced in the brain.

Beth: Exactly! Sometimes bodily damage will cause pain; sometimes bodily damage does not cause pain. And, sometimes pain can exist without any damage to the body; this phantom pain is keenly felt but there is no bodily cause. So pain is not always embodied but sometimes it is. When the body is damaged and the brain creates an experience of pain, this is the brain creating a controlled hallucination that matches reality. When the body is not damaged and yet the brain creates an experience of pain, this is a case of an uncontrolled hallucination: the brains simulation is not matching reality. This is one of the problems that I mentioned earlier when the brain is not updating the simulations correctly. I believe emotions are controlled hallucinations, although I admit uncontrolled hallucinations could arise sometimes creating a disembodied emotion.

Craig: Right, when I have a client with pain, and there is obvious trauma to the body, I can surmise that if we fix the trauma, stitch the wound for example and give some painkillers, the pain will go away. When the client has pain but does not have any trauma, after ruling out potential tissue damage, I move on to look for non-physical causes. The source of the pain is usually from one cause or the other.

Beth: So, even with physical trauma as the cause of the pain, would you say the pain is only coming from the brain?

Craig: Yes! Yes, I would because it is the brain that creates the pain. The signals from the body, whether they are chemical, like substance P, or electrical via the nociceptors’ nerve endings, are not pain. Pain is what the brain creates after receiving these inputs.

Beth: Today in class, the teacher offered Lotus Pose, but not everyone can do Lotus Pose, so she warned, “If you feel any pain or discomfort in your knees, stop and sit cross-legged.” Even though she said “pain in the knees”, you don’t criticize her despite your belief pain is created in the brain. Why do you not criticize that statement but you do when she says, “Anger is in the hips”?

Craig: Pain is tricky, I will admit. Sometimes there is damage in the knee which the brain will notice and create the sensation of pain there. But, it is still the brain that creates the pain.

Beth: But, if you ask a student, “where is the pain?” they will point to their knees. For them, the pain is definitely in their knees. To say, “no—you’re wrong. Your pain is all in your head” will seem obviously incorrect to these students. In the same way, for some students, doing hip work in yoga triggers strong emotions. Remember the study from Finland where they mapped all the places in the body where people felt their emotions. You wouldn’t tell a student with knee pain that they are mistaken and that the knees can’t create pain, so why tell a student who is feeling angry that it is not coming from her hips?

Craig: Because hips don’t store anger! Look, clearly if someone is feeling pain somewhere, I won’t tell them that are not, even though I know the underlying process is the brain creating the sensation. But, I will draw the line at pretending emotions are in the body.

Beth: Let’s return to predictive processing. The brain generates our experience of pain—yes, but the signals are coming from the body. Red came from the strawberry; pain comes from the body. Now, when we experience pain but there is no damage to the body, we have a prediction error. The brain is hallucinating something that does not exist. This doesn’t mean the experience is not happening: people can still feel the pain even when there is no tissue damage. But, where there is tissue damage, the cause of the pain is in the body and that is where people will feel the experience is coming from.

With emotions, the same thing happens. When the body is in a particular state, our interoception picks up on the signals, perhaps some combination of position of the joints, tension in the muscles and fascia, carbon dioxide levels in the blood, heart rate, etc. These signals are noted by the brain, which then generates a simulation of the emotional state of the body. We experience an emotion based on the state of the body. Just as someone can say they feel pain in their knee, someone can say that whenever they move their hips in particular ways, anger seems to erupt.

You and I can say, “No: pain is created by the brain and it is not in your knees” and “No: emotions are created by the brain and there are no issues in your tissues”, but we cannot deny that the students are experiencing the pain in their knee and anger when they do hip work.

Craig: I am listening, but I am not convinced. There are many theories about consciousness, so who is to say this model of predictive processing is correct. Even Charles Darwin proposed that emotions are hard-wired into the brain.

Beth: Ah, well…if you want to go back in history, yes, that was Darwin’s view, but later William James, a pillar of early psychology, thought that emotions arose due to our perception of changes in our bodies. We don’t cry because we are sad, we feel sad because we are crying! The body’s state is the emotion and that is what we perceive.5 We have learned a lot more about our brains and bodies since the 1800’s but I don’t think we have a final definitive answer yet as to what exactly constitutes an experience, let along how we experience emotions.

Craig: So you are saying that our brain can only make predictions about the outside world, and in this case, even our body is considered the outside world by the brain. This prediction, or simulation, is generated based on sense inputs which include many facets of interoception. These predictions form our experience of the outside world, which I agree with. That is why I said emotions are in the brain. But you are saying that our brain’s experience of emotion is the simulation of a real emotion occurring in the body.

Beth: Good summary

Craig: Hmmm…well, maybe. I will have to think about that a bit more. Still, I don’t like it when yoga teachers use fluffy poetry to explain something that the science doesn’t agree with. And she certainly didn’t offer any explanation about predictive processing!

Beth: Well, I don’t like fruity, woo statements either, and unfortunately, it is sometimes offered in some yoga classes. I am pretty sure the teacher has never heard of predictive processing before, but you have to admit that “issues in the tissues” sounds pretty cool. And science has not proven that it is incorrect, at least not yet. If someone feels an emotion while in a particular yoga pose, it is as hard to tell them that the emotion is not coming from their hips as it is to tell them that a pain is not in their knees.

The cups of chai long emptied, Beth and Craig surrender their table to a few other yoga students who just finished their class. Wherever emotions reside, and Beth is still convinced they are embodied and only sensed by the brain, her weekly yoga classes always leave her feeling calm, serene and happy. She knows that Craig enjoys the classes too, despite his misgivings about the teacher’s penchant for poetic language. She turns to Craig and smiles:

Beth: See you next week?

Craig, ginning: Yep! Wouldn’t miss it.

– Postscript——

For anyone who would like to look deeper into the topic of emotions, predictive processing and how the mind creates our experiences, I highly recommend the two books cited in the endnotes: Being You by Anil Seth (2021) and How Emotions Are Made by Lisa Feldman Barrett (2018). They are fascinating and quite easy to digest. In Barrett’s book, you will learn that emotions are also contextual and cultural: they are not just mental but have biopsychosocial elements. Their construction and our experience of them are multifaceted.

[2] Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions are Made, Mariner Books, 2017, page 19.

[3] Ibid, page 23.

[4] Nummenmaa L, Glerean E, Hari R, Hietanen JK. Bodily maps of emotions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Jan 14;111(2):646-51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321664111. Epub 2013 Dec 30. PMID: 24379370; PMCID: PMC3896150.

[5] Anil Seth, Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, Dutton, 2021, page 183.