By Bernie Clark, October 20, 2021

Did you know that your yoga practice may be reducing chronic inflammation and slowing down your body’s aging? Chronic inflammation has been so closely associated to accelerated aging that a term was coined to link the two: inflammaging. Mechanical stresses and mental relaxation that occur during your yoga practice have been found to moderate and even stop many of the causes of inflammaging. No wonder your friends tell you that you look so good! There is a lot more to yoga than maintaining flexibility!

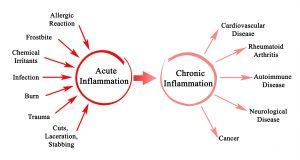

We have all felt the discomfort of an injury. The damaged area becomes painful (called dolor), hot (calor), red (rubor) and swollen (tumor). These are the four hallmarks of acute inflammation (AI) and they are good. We need this response. The body is attempting to reduce the spread of damage (thus the swelling which may cause pain) and increase blood flow to the area (which creates the redness and heat). This response helps to neutralize any infection and remove damaged tissue while stimulating new tissue growth. AI is a healthy, natural reaction to tissue damage. Chronic inflammation (CI), on the other hand, is not healthy.

Chronic inflammation is acute inflammation that has not been turned off. Our immune system continues to act as if the body is damaged or under attack. Cells continue to release special messengers (called cytokines and chemokines) that perpetuate the state of inflammation. This sterile form of inflammation can accelerate aging through reducing our healing response, degrading tissue health and stiffening fascial networks. When our tissues and our organs are not working optimally, we exhibit accelerated signs of aging, thus the term inflammaging.[i] Chronic inflammation leads to accelerated aging.

Causes of chronic inflammation

Research is still uncovering all the reasons that we become chronically inflamed. Injuries or infections may create too much cellular debris, which are bits of broken cells, floating throughout our body that need cleaning up. Often older cells refuse to die when they are too old to contribute to the well being of the body, a state know as cellular senescence. Senescent cells pump out inflammatory cytokines. Benign or helpful bacteria, for example in our digestive tract, may secrete inflammatory chemicals. As we age we tend to create and maintain a greater number of fat cells. These fat cells can also secrete inflammatory messengers. Our immune system may become over-stimulated and contribute to CI instead of controlling it. Additionally, the mitochondria within our cells, the “power plants” of each cell, may produce too many free radicals.

Normally, free radicals are quite useful. They are produced during acute inflammation to attack and destroy invading bacteria, parasites and fungi. But, if there are no invaders, they can attack healthy cells. If this happens, the body reacts as if it is under attack and responds by inflaming the area. However, this results in more free radicals being released, which makes the inflammation worse, thus creating the cycle of chronic inflammation.

Cortisol: the Goldilocks’ molecule

Our immune system has two parts: the frontline or innate immune system and the backline or adaptive immune system. The innate system turns on quickly and gives broad based protection against invading pathogens. This is what happens during acute inflammation. The body inflames the damaged area (dolor, calor, rubor and tumor occurs), immune cells arrive to destroy invaders and remove damaged cells, fibroblasts show up to stiffen the region and create a scaffold for stem cells which help rebuild the damaged tissue.

The adaptive immune system is slower to get going than the innate system. If viruses or bacteria manage to avoid the frontline troops, then the backline research and development lab gets busy to develop weapons that will take out the invaders. This takes a few days but when the adaptive system is fully up and running it will create specific immune cells (such as T and B cells) and antibodies. These directly target the pathogens and eliminate them.

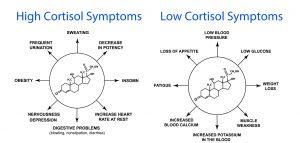

Cortisol is a critical hormone for health. It has several functions. Made from cholesterol and secreted by the adrenal glands, it helps the liver to produce more glucose (called gluconeogenesis) and helps our muscles and brain take up glucose effectively. This is essential during a fight or flight, sympathetic response. (Our cortisol levels are naturally highest in the morning: it is like an internal cup of coffee that gets us going.) From the immune perspective, cortisol helps to turn off inflammation. It induces cellular death (apoptosis) of the T and B immune cells and reduces white blood cell (specifically, neutrophil) migration.[ii]

Cortisol is a Goldilocks’ hormone. We need just enough to get us up in the morning, to prepare the muscles to burn fuel and to turn off chronic inflammation. However, too much cortisol can persistently reduce immune response and delay healing. If we continue to over-produce cortisol, the body starts to ignore it. Similar to a type II diabetic whose is insulin intolerant, we can become cortisol intolerant. When the body no longer responds to cortisol, inflammation persists, the adrenals have to produce cortisol to control inflammation, but this can lead to the body becoming more intolerant, causing the adrenals to have to produce even more. Eventually the whole system crashes to a halt and we no longer have any way to control inflammation, which leads to the state of CI.[iii]

Other ways to control and eliminate chronic inflammation

Fortunately, there are other ways to help control and reduce CI and two of these ways occur during our yoga practice: exercise and stress reduction. Chronic psychological stress combined with simply growing older reduces immune function. Our immune system ages faster when we are chronically stressed which reduces our ability to control CI, which in turn reduces our immune system further. It is a vicious cycle: the older we get, the worse we get. The worse we get, the faster we age. Psychological stress can wear many disguises: being in a troubled relationship; feeling lonely; negative social interactions; and many others. Even having one bad night’s sleep can increase neutrophil counts, which reduce their function. [iv] Fortunately, yoga practice, meditation and a good sense of humor can reduce psychological stress.[v] One study found that five weeks of Yin Yoga limited the negative health effects associated with psychological stress.[vi] Another study followed participants doing 90 minutes of asanas, pranayama and meditation 5 days a week for 12 weeks and found significantly lower levels of cortisol and reduced inflammation (along with many other improved anti-aging markers).[vii]

The physical aspect of yoga

The physical aspects of our yoga practice may be just as important for controlling inflammaging as the psychological aspects. Regeneration of tissues is complex and there is a lot going on beneath the surface: immune cells such as leukocytes, monocytes, macrophages and T cells and cytokines are all active to stimulate muscle stem cells (called satellite cells), grow new blood vessels (angiogenesis) and create new fascial networks (called ECM remodeling) while reducing fibrosis.[viii] Neutrophils proliferate in muscles that are damaged. That is good: neutrophils kill pathogens and clear out damaged tissues. However, if they linger too long, they interfere with muscle repair and promote inflammation.

Mechanical stresses can reduce inflammation! One study employed mechanical stresses, in the form of mechanotherapy, to remove neutrophils, which led to quicker healing, bigger muscle fibers and greater strength.[ix] In this case the mechanical therapy was done on mice and was performed by a machine but the results are quite suggestive. The mechanical loading cleared the tissues of the inflammatory cytokines and enhanced muscle regeneration.

Another murine study (this time using rats) found that a whole body stretch for 10 minutes, twice a day, over 12 days significantly reduced inflammation that had been induced in the lower back.[x] Even more interesting was a follow up study that found that one gentle stretch held for 10 minutes/day over four weeks reduced breast tumour volume by 52% compared to a control group. This yin-like stretching reduced fibrosis and connective tissue inflammation that contribute to tumor migration.[xi]

Fascia is an active participant in immune function

If chronic inflammation continues unabated, our connective tissue becomes stiffer and fibrotic. These conditions can lead to tumor invasion and growth. Fortunately, exercise and stretching can prevent or reduce this.

During vigorous exercise, blood vessels, which are wrapped in fascial sheaths called basement membranes, expand to allow more oxygen and nutrients to flow to the hungry muscles, but this also allows cytokines, immune cells and cellular debris to flow out of the muscles and neighbouring tissues. Blood plasma flows through the fascial membranes surrounding these tissues into the loose connective tissue (called the interstitium). With external stress, caused by exercise, massage or yoga, plasma flows through the interstitium sweeping along pathogens, pre-cancer and cancerous cells, as well as other inflammation provoking messenger molecules. These are deposited up in the lymphatic system. In the lymph nodes the pathogens and cells are neutralized and sent to the liver for elimination.[xii]

When I first started practicing yoga, my teacher, Shakti Mhi, told me that yoga could detoxify the body. Years later I was told that this was nonsense. Only the liver, kidneys, lungs and possibly the skin remove toxins from our tissues. Physical asana practice could not do anything to release or remove toxins. Today, the pendulum has swung again and researchers are discovering that exercise, massage, stretching and yoga do affect our fascia, muscles, blood system, immune system, nervous system and organs, helping to mobilize and remove toxins, pathogens, pre-cancerous senescent cells and cancerous cells. Yoga does indeed detoxify the body and in the process helps to reduce chronic inflammation which leads to premature aging.

Anti-inflammation without the aid of steroids or painkillers! What a lovely bonus from your yoga practice. No wonder you love it so much.

_____________________________________

[i] Professor Franceschi introduced the inflammaging concept in 2000. See Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 Jun;69 Suppl 1:S4-9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. PMID: 24833586.

[ii] Thau L, Gandhi J, Sharma S. Physiology, Cortisol. [Updated 2021 Feb 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/

[iii] Cortisol intolerance is one reason that cortisone shots are a last resort for treating chronic inflammation of a joint. It will work once or twice, but after a few courses of treatment, the body begins to ignore the cortisol and then there is no easy way to manage the inflammation.

[iv] Morey JN, Boggero IA, Scott AB, Segerstrom SC. Current Directions in Stress and Human Immune Function. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:13-17. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.007

[v] Deshpande, Dr. Revati, A Healthy Way to Handle Work Place Stress Through Yoga, Meditation and Soothing Humor (May 9, 2012). International Journal of Environmental Sciences, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 2143- 2154, 2012, doi:10.6088/ijes.00202030097 Code: EIJES3202 (ISSN 0976 – 4402), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2103483

[vi] Daukantaitė D, Tellhed U, Maddux RE, Svensson T, Melander O. Five-week yin yoga-based interventions decreased plasma adrenomedullin and increased psychological health in stressed adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200518. Published 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200518

[vii] Tolahunase M, Sagar R, Dada R. Impact of Yoga and Meditation on Cellular Aging in Apparently Healthy Individuals: A Prospective, Open-Label Single-Arm Exploratory Study [published correction appears in Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:2784153]. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:7928981. doi:10.1155/2017/7928981

[viii] Zügel M, Maganaris CN, Wilke J, Jurkat-Rott K, Klingler W, Wearing SC, Findley T, Barbe MF, Steinacker JM, Vleeming A, Bloch W, Schleip R, Hodges PW. Fascial tissue research in sports medicine: from molecules to tissue adaptation, injury and diagnostics: consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Dec;52(23):1497. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099308. Epub 2018 Aug 2. PMID: 30072398; PMCID: PMC6241620.

[ix] Seo BR, Payne CJ, McNamara SL, Freedman BR, Kwee BJ, Nam S, de Lázaro I, Darnell M, Alvarez JT, Dellacherie MO, Vandenburgh HH, Walsh CJ, Mooney DJ. Skeletal muscle regeneration with robotic actuation-mediated clearance of neutrophils. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Oct 6;13(614):eabe8868. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abe8868. Epub 2021 Oct 6. PMID: 34613813.

[x] Corey SM, Vizzard MA, Bouffard NA, Badger GJ, Langevin HM. Stretching of the back improves gait, mechanical sensitivity and connective tissue inflammation in a rodent model. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029831. Epub 2012 Jan 6. PMID: 22238664; PMCID: PMC3253101.

[xi] Berrueta L, Bergholz J, Munoz D, Muskaj I, Badger GJ, Shukla A, Kim HJ, Zhao JJ, Langevin HM. Stretching Reduces Tumor Growth in a Mouse Breast Cancer Model. Sci Rep. 2018 May 18;8(1):7864. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26198-7. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2018 Nov 16;8(1):17226. PMID: 29777149; PMCID: PMC5959865.

[xii] See Fascia, exercise and oncology, by Susan Shockett and Thomas Findley in chapter 18 of Fascia in Sport and Movement, Second Edition, Handspring Publishing, 2021, page 202.