By Bernie Clark

April 25, 2025

Adapted from Your Spine, Your Yoga

Have you ever seen someone walking with their upper back rounded and shoulders hunched forward, almost as if carrying the weight of the world, or at least the weight of their years? That forward curve of the spine is called kyphosis—and when it becomes excessive, it’s known as hyperkyphosis.

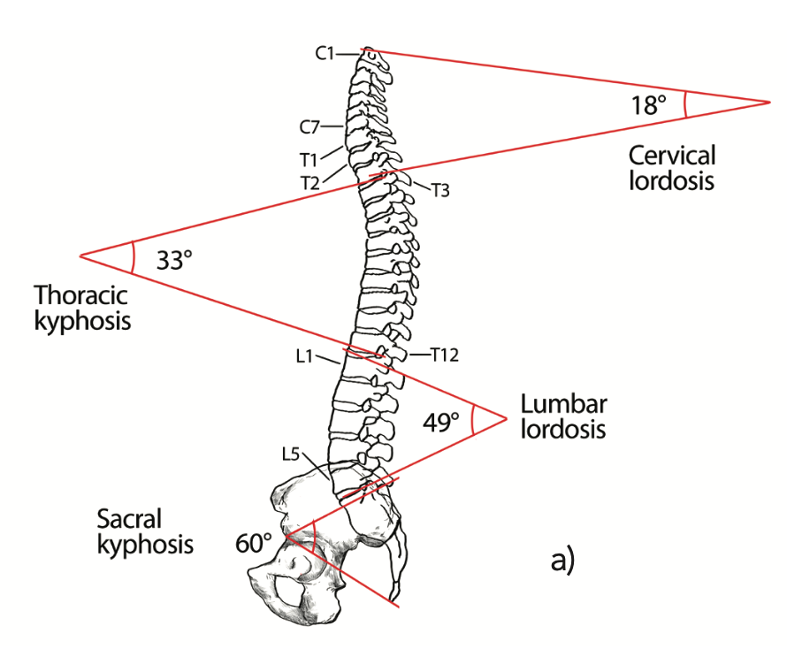

Normally our spine has four distinct curves, as shown in figure 2. On average the upper back, called the thoracic spine, has a curve of about 33°. It begins around the third thoracic vertebra (T3) and reaches its maximum curvature just behind the heart, around the 7th or 8th thoracic vertebrae. When kyphosis becomes greater than 45°, mobility is impaired and the risk of falls increases. This is the condition known as hyperkyphosis,1 also called a dowager’s hump or gibbous deformity.

You might think osteoporosis is always to blame, but surprisingly, most people over 60 who develop hyperkyphosis don’t have osteoporosis at all. 2 Hyperkyphosis can be caused by osteoporosis, which may lead to vertebral fractures (osteoporosis accounts for about 40% of vertebral fractures), but causes vary and may include degenerative disc disease (unrelated to osteoporosis), chronically held flexed postures, reduced bone density, neuromuscular issues affecting abdominal tone, 3 spinal extensor weakness, calcification of the anterior longitudinal ligament, and degradation in posture due to impaired eyesight, balance, or proprioception. 4 The condition can be congenital or may develop over years of a chronically flexed posture.

As the upper back rounds, the ribcage compresses like a slowly closing accordion, making it harder to take full, deep breaths, especially for people with kyphosis greater than 55°. This decreased lung capacity may be due not only to a smaller chest cavity but also to the fact that as the ribs come closer together, the intercostal muscles become shorter and weaker.5

As the thoracic spine curves more deeply, body height is lost: a 15° increase in kyphosis results in a loss of 4 cm.6 Shortened hip flexors and pectoral muscles are also hallmarks of this condition, but it is unknown whether short, tight muscles cause the condition or vice versa.

Hyperkyphosis can cause someone’s center of gravity to move forward, requiring compensation in other areas to maintain balance. Lumbar lordosis will increase, where possible, and the pelvis will tilt posteriorly. These accommodations will bring the line of the center of gravity back behind the femurs’ heads. While this will improve balance, it will also increase the stress on lumbar discs and vertebrae and can lead to degeneration. To maintain this posture, chronic muscular effort is required, which can also lead to chronic pain.7

Combatting hyperkyphosis

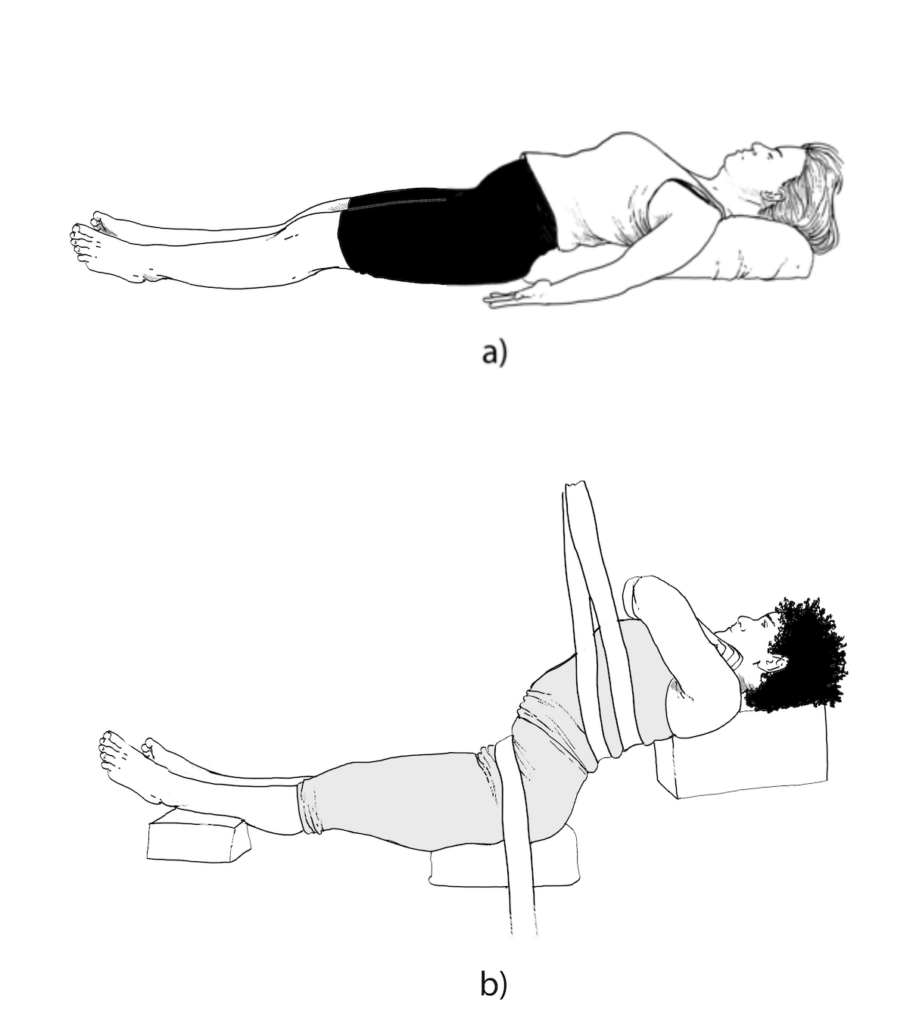

There are no standardized treatment protocols for hyperkyphosis.9 Figure 3 shows two types of backbending practices used in yoga therapy. One is a familiar reclined pose over a bolster, while the other is a deeper, more sustained traction method. Figure 4 shows how a bolster can be used for a reclining Half-Saddle pose, often used in yin yoga classes.

It is important to understand the cause of any problem before devising a treatment plan. When the problems are related to posture or muscular deficits, there is some indication that yoga may be helpful. One study of women over 60 examined the effects of a regular hatha yoga practice that included reclining backbends, prone back-strengthening exercises, Balancing Cat,10 other easy poses on hands and knees, and easy standing postures. The results of taking classes twice a week for 12 weeks were significant, although modest—about a 2% reduction in the kyphotic curve.11 A longer study of men and women conducted over 24 weeks with classes three times a week created a 4.4% improvement.12 In addition, the yoga students reported much less back pain than the control group.

|

Not every yoga pose is appropriate for someone with advanced kyphosis. Movements should be introduced gradually and mindfully, ideally under the guidance of a knowledgeable teacher or therapist. |

In the longer study, postures included all those cited in the shorter study, but since there was more time, additional postures were introduced. As with most hatha yoga practices, coordinated breath work accompanied postures to open the chest, while others were used to strengthen the supporting posterior muscles (rhomboids and erector spinae). The abdominals and quadriceps were also targeted for strengthening. If you’re a yoga teacher, you might try these movements yourself—notice how they affect your posture, your breath, and even your sense of presence.

Therapists outside of the yoga realm have also addressed hyperkyphosis through similar means: strengthening the back body, lengthening the front body, and training for appropriate posture and alignment of the spine. Strengthening exercises include prone trunk lifts (Salabhasana variations), side plank poses (easy Vasisthasana) and other hands-and-knees postures.13 Some therapists include long-held traction for the back, as shown in figure 3b, incorporating a more yin-like approach of holding this position for up to 20 minutes.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but the evidence is encouraging: gentle yoga—especially practices that open the chest and strengthen the back—can help restore posture, breath, and confidence. Even if the curve remains, many students report a return of spaciousness, ease, and a renewed sense of vitality.

_______________________

1 Some researchers use a 40° kyphotic angle as the beginning of the condition of hyperkyphosis.

2 See D.M. Perriman et al., “Thoracic Hyperkyphosis: A Survey of Australian Physiotherapists,” Physiotherapy Research International 17.3 (2012): 167–78.

3 See W.B. Katzman, L. Wanek, J.A. Shepherd, and D.E. Sellmeyer, “Age-Related Hyperkyphosis: Its Causes, Consequences, and Management,” Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 40.6 (2010): 352–60, doi:10.2519/jospt.2010.3099.

4 Ibid

5 See E.G. Culham, J.A. Jimenez, and C.E. King, “Thoracic Kyphosis, Rib Mobility, and Lung Volumes in Normal Women and Women With Osteoporosis,” Spine 19.11 (1994): 1250–5.

6 See K.E. Ensrud, D.M. Black, F. Harris, B. Ettinger, and S.R. Cummings, “Correlates of Kyphosis in Older Women: The Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45.6 (1997): 682–7.

7 See Jean Legaye and G. Duval-Beaupère, “Sagittal Plane Alignment of the Spine and Gravity: A Radiological and Clinical Evaluation,” Acta Orthopaedica Belgica 71 (2005): 213–20.

8 The traction image is based on figure 4 in Jason E. Miller, Paul A. Oakley, Scott B. Levin, and Deed E. Harrison, “Reversing Thoracic Hyperkyphosis: A Case Report Featuring Mirror Image® Thoracic Extension Rehabilitation,” Journal of Physical Therapy Sciences 29 (2017): 1264–7.

9 See W.B. Katzman et al. “Study of Hyperkyphosis, Exercise and Function (SHEAF) Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Multimodal Spine-Strengthening Exercise in Older Adults With Hyperkyphosis” Physical Therapy 96.3 (2016): 371–81, doi:10.2522/ptj.20150171.

10 Come onto all fours, as you would do for Cat Pose, and then place your spine as close to neutral as you can manage, extend one arm forward then lift and straighten the opposite leg backwards. Hold for 20 to 30 seconds and switch sides. Repeat again with a shorter hold.

11 See Gail A. Greendale, Anna McDivit, Annie Carpenter, Leanne Seeger, and Mei-Hua Huang, “Yoga for Women With Hyperkyphosis: Results of a Pilot Study,” American Journal of Public Health 92.10 (2002): 1611–14.

12 See G.A. Greendale, M.H. Huang, A.S. Karlamanga, L. Seeger, and S. Crawford, “Yoga Decreases Kyphosis in Senior Women and Men With Adult Onset Hyperkyphosis: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57.9 (2009): 1569–79, doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02391.x.

13 See Katzman et al., “Study of Hyperkyphosis.”