By Bernie Clark, June 24th, 2020

Can I do yoga every day? The answer is “yes!” and “no!” and “maybe!” This is a concern for a lot of people, whether they are new to yoga, beginning to lift weights or taking up running. “How often should I practice?” Sometimes the question is inverted into, “How long should I rest between sessions?” The short answer, while true, is not so helpful: it depends! A longer answer may be more satisfying.

Specifically, it depends upon (1) the type of practice you are doing and (2) your intention in practicing—meaning the goal you are trying to achieve. There are many possible intentions and you may actually have two or more in mind at any given time. For example, you could intend to:

- increase/maintain strength

- increase/maintain endurance

- increase/maintain flexibility

- increase/maintain mobility

- increase/maintain speed and power

- increase/maintain bone mineral density

- maintain or regain health and well-being

- increase/maintain performance in a specific sport or activity

Depending upon your intention, the nature of your practice and your own biological uniqueness, how often you can practice and how long you should rest between practices will vary.

The value of rest

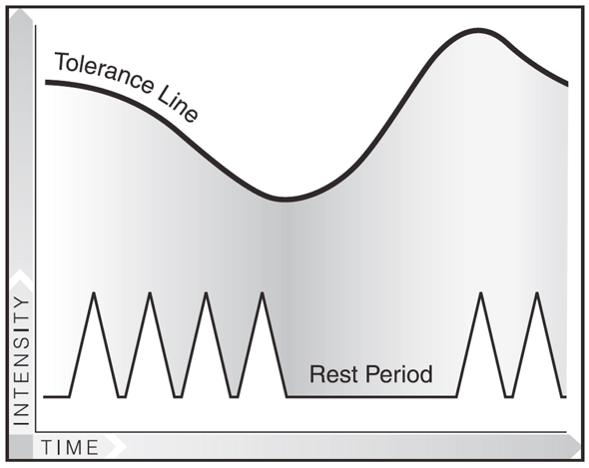

Resting after a stress gives the body a chance to recover and become better able to deal with subsequent stresses of a similar nature. Professor Stuart McGill, a spine biomechanic, refers to the balance between sufficient stress to generate an adaptation and sufficient rest to avoid degeneration as the “biological tipping point.”[1] Figure 1 illustrates the trade-off between stress and rest. When we apply a stress to our tissues, they become weaker. We can stress the tissues a lot for a very brief time, or we can apply a mild stress held for a long time, or we can apply a moderate amount of stress repetitively. All of these can cumulatively reduce the tissue’s tolerance. Once the stress exceeds the tolerance, the biological tipping point has been passed, and injury occurs.

However, if we allow a refractory period (which is a fancy term for “rest”), the tissues get a chance to adapt to the imposed stress and become stronger.[2] (Stress in this context could also be called “demand” or “load.”) This is shown in the right-hand side of figure 1. After the rest period, the tissues you just used become more usable.[3] How long the rest period should be depends upon the type of stress you are applying and which tissues you are targeting.

Resistance training

During aerobic or strength-building exercises, fluids are lost, energy is consumed, body temperature rises, the heart and lungs work harder and muscle tissues may become damaged at microscopic level. The recovery period must be long enough to restore homeostasis, or balance, to all these systems.[4]

When you lift weights to build strength, you need to choose a resistance level that adequately stresses the muscles. When the stress is sufficient, microscopic damage occurs within these tissues. The body responds with inflammation and muscle damage markers that stimulate healing.[5] If it is your first time working out, you may also experience fatigue and pain, often called delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). Subsequent bouts of exercise will likely not result in more DOMS.

Resistance exercise and high-intensity aerobic exercises can significantly stress skeletal muscle, and they may cause damage to the fascial wrappings of the muscle cells, contractile proteins within the muscle, and connective tissue around the muscle. These changes will impair the muscle’s ability to generate forces, and decrease the transport of glucose into the muscle cell. This diminishes the muscles’ capacity to replenish glycogen stores. Until these stores are replenished, the muscle will not function optimally. How long does that take? It depends! The general rule of thumb is to let the muscles rest for one to two days before working the same ones again.

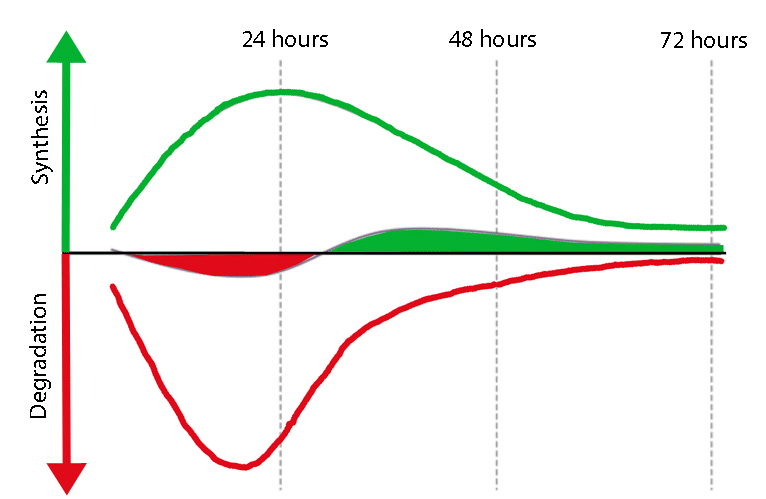

Stressing and resting fascia

At a fascial level, exercise can create strain (elongation) within the tendons connected to the activated muscles and to the fascial bags around and within the muscles. (The fascial wrappers, or bags, around and within a muscle are called the epimysium, perimysium and endomysium.) Fascial tissues undergo remodeling after stress, just as muscle cells do. The synthesis of new collagen fibers can peak within 24 hours after exercise but continues for almost three days.[6] However, along with regrowth there is a parallel degradation of existing collagen, and this peaks earlier than the generation of new fibers. The net effect of these two functions, synthesis and degradation, means that for the first 24 hours, the tendons and myofascia are actually weaker, and only after about 36 hours does a net gain in collagen begin. (See figure 2.) This is a good reason for waiting at least two days before exercising the same area again, and perhaps even three.

Recovery times from strength and aerobic training depend upon nutrition as well as rest and recovery practices. Nutrition includes replacing lost fluid,[7] restoring glycogen levels (Gatorade is highly regarded) and consuming protein (ideally with moderate amounts of carbohydrates.[8]) Several practices can diminish pain, reduce inflammation and speed up muscle rebuilding and glycogen stores. Massage is favored, but compression garments and cold therapy have also shown modest benefits.[9] Ironically for yoga teachers, stretching has not proven effective and may actually increase DOMS.[10] (This is theorized to be because stretching further damages the muscle tissues.) Despite all this, normal human variation is also a factor, which means no single prescription will work for all bodies.[11]

Several generalizations are offered in the fitness community. In general, women are believed to recover faster than men.[12] In general, bigger muscles (think of the lower body) take longer to recover than smaller muscles (upper body.)[13] It is often recommended that you exercise one region of the body on one day and do another area on the second day, which gives the first region time to recover. By the third day, you should be ready to work the first area again. However, this is not my own personal experience! At age 66, I do much better if I take at least three to four days off after weight training a specific area—and sometimes, when I take a full week off, I feel much stronger than when I train twice a week. You can only determine your ideal rest period through trial and error, paying close attention to the differences you observe.

Endurance training

The heart, lungs and other parts of the cardiovascular system also need time to recover after a workout, but unlike our skeletal muscles, the cardiovascular system can return to normal quite quickly. Indeed, what limit how many aerobic training sessions per week are advisable are not the heart and lungs but the muscles we use to stress the heart and lungs. For this reason, many runners find it perfectly okay to run every day, as long as their other body parts are not complaining. The heart is not the limiting factor.[14]

The heart does need some time to recover, and it is not uncommon for many people to experience low blood pressure (hypotension) for a few hours after an aerobic workout. Extreme symptoms can include a light-headed feeling, blurred or tunnel vision and loss of consciousness. Hypotension after exercise has several causes.

- The sympathetic nervous system, which raised the heart rate during exercise, shuts down, and the parasympathetic system takes over, reducing heart rate and blood pressure.

- Blood vessels dilate after exercise; this is called vasodilation and can last for several hours. It occurs mainly in the bed of capillaries inside the muscles, causing blood to pool. Less blood in circulation reduces blood pressure. Vasodilation within the muscles is thought to be due to the release of histamines during exercise. Antihistamines have been shown to reduce this action and increase post-exercise blood pressure.[15]

- During exercise, muscle contraction helps to circulate the blood. This is known as the muscle pump. Clearly, after exercising, the muscles are no longer helping to pump the blood, contributing to low blood pressure.

- Dehydration can also reduce blood volume. If your workout was particularly sweaty, rehydrating carefully after working out, or even hydrating extra beforehand, may reduce the post-exercise effects.

The loss of the muscle pump is one reason that post-workout cool-down exercises may be beneficial. The muscles stay active, helping to continue moving the blood so that the heart doesn’t have to do all the work. (This is also a reason many weightlifters like to walk around between sets of lifting: the movement keeps the blood pressure higher. Sitting after lifting can create a bigger drop in blood pressure. I personally find it helpful to walk quickly between sets: lifting my knees really high. I have found this keeps my blood pressure raised.)

Flexibility/mobility training

The more muscular your mobility training, the more time off between sessions you may require. If your flexibility training is a gentle Hatha yoga practice, this can safely be done daily. Indeed, gentle yoga practices are recommended as something to do during the rest days between aerobic or resistance training sessions. However, if you are going for extreme flexibility development, the stresses you are placing on the connective tissues may require longer rest periods between sessions. And, it should be pointed out, that flexibility develops more slowly than strength or endurance. Indeed, it can take years for a significant portion of the collagen in our fascial tissues to be remodeled.

As shown in figure 2, collagen, the primary component of many fascial tissues, takes time to be synthesized. If you are working at the edge of your abilities and range of motion, you may need two or three days off between practice sessions. This could apply to a yoga practice, if you are working intensely at increasing range of motion. Longer held yin yoga postures near end ranges of motion may require longer rest periods. However, if your yin yoga practice is milder, a daily practice may be easily tolerated and quite beneficial.

Bouncing training (plyometrics)

If your intention is to regain or maximize the spring in your step, working out just two or three times a week may be optimal. Many sports rely upon the springiness of our fascia. Throwing a ball or javelin, kicking, running, jumping, and swinging a racket or golf club all rely upon a loading up the springs within our fascia (the tendons, ligaments and myofascia) and sudden releasing this pent-up potential energy.

In his book Fascial Fitness, Robert Schleip explains that the collagen proteins making up most of our fascial fibers have a crimp: a W-shape pattern. The more this pattern appears, the better adapted we are to elastic recoil movements found in sports, dancing or simply skipping rope.[16] He goes on to describe different forms of training for fascia:

- muscle-engaged stretches (active), which load the tendons (such as a bicep curl, where the muscle shortens but a stress slightly elongates the tendons)

- muscles-relaxed stretches (passive), which stress and stretch the muscles and the fascia elements in parallel to them (the myofascia) but not the tendons

- active resistance stretches, where the muscles are engaged but the myofascia and tendons are stretch loaded

The final form of exercise is typical of plyometric or bouncing trainings, such as repetitive jumping, skipping rope, springing pushups against a wall or countertop, etc. These bouncy movements are excellent at rebuilding the crimp in the collagen. But as we have seen, it takes time to remodel collagen. These practices need to be done for only 10 minutes or so, at most two to three times per week.

Building bone

When a bone is broken, repair occurs in stages. First, a provisional bridge, called a soft callus, is formed between and uniting the ends of the bone. This primary callus is formed of cartilage. The next stage reabsorbs the cartilage, replacing it with collagen fibers, blood vessels and tissue-building cells, forming a new, compact bone matrix, called a secondary callus. Finally, mineralization occurs around the collagen scaffold, and the callus is reabsorbed. This final stage, called remodeling, can take months or years to complete.

Similar remodeling processes occur in healthy bone as well. It is an ongoing process, at the microscopic level, of breaking down and absorbing old bone and depositing new bone. During the resorption phase, the bone is weaker than normal. It takes time for the formation stage to complete. During the weakened stage, further stress on the bone could delay repairs and further damage the bone. Rest is very important. How much rest depends upon the person and the amount of stress/level of exercise they have been doing. Stuart McGill suggests four to five days of rest is a good rule of thumb when doing significant resistance training.[17]

So, how long should you rest between exercising?

By now, you know that it depends upon you, what exercises you choose to do, and why you are doing them. If your practice is gentle, daily exercise is most likely not a problem. This can apply to gentle yoga practices, yin yoga or a short daily run. If your intention is to develop strength, a day or two off between working the same area is a good starting point, then see how you feel from there. If you are working on explosive, powerful, springing movements, you may want to limit yourself to two to three plyometric sessions a week. If you are working on serious weight lifting and resistance training requiring very strong bones, or you are recovering from a bone fracture, you may need to rest four to five days between sessions.

As always, practice with both intention and attention. With careful observation, you will discover what works best for you.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Listen to Professor McGill explain the biological tipping point in his own words in a video hosted by Yoga International. Visit this page [https://yogainternational.com/ecourse/your-spine-your-yoga-the-course] and scroll down to the video.

[2] There is a technical term used to describe this ability: SAID, which means “specific adaptation to imposed demand.”

[3] I first heard, “The tissues you just used become more usable,” from Sarah Powers.

[8] Peake, “Recovery After Exercise.”

[9] Dupuy et al., “An Evidence-Based Approach.”

[15] Romero, Minson, and Halliwill, “The Cardiovascular System After Exercise.”