By Bernie Clark, October 18, 2022 – Excerpted from the book Your Upper Body, Your Yoga

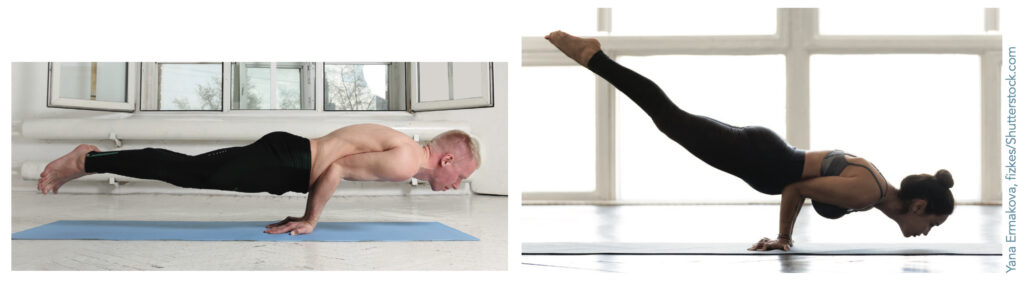

Should you bend your fingers when your palms are on the floor? Can you easily place your palms flat, fingers straight while doing Plank Poses, Handstands, Crow Pose, or any posture that requires full wrist extension while the hands are on the floor? Some students can, but many and probably even most cannot. Why is this and what can these students do if they can’t keep their fingers and palms flat on the floor?

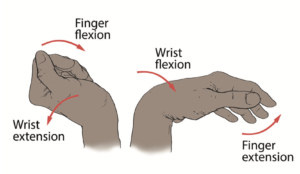

For many yoga students, extension of the wrist is limited by tension. When the wrist is fully extended—for example, in arm balancing postures that require hands on the floor—but the hands and fingers are flattened, extension of the fingers will pull the wrist out of its full extension. However, when the student flexes the fingers, this reduces the flexion stress across the wrist, which allows full extension to be achieved. In other words, when the fingers are flexed, the wrist can extend to the limits allowed by compression. Once compression is reached, the wrist will not extend further. But if the hand and fingers are not allowed to flex, the wrist may not achieve its full range of extension.

Figure 2 shows how tension in the finger flexors may restrict wrist extension. This is known as tenodesis action. Fully extending the wrist can cause passive flexion of up to 50° at the digits’ proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints (those are the middle creases in your fingers) and up to 20° at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (those are the creases closest to the fingertips).1 Tenodesis action may also be why the yogis performing Peacock Pose (Mayurasana) in figure 1 have their fingers flexed: if they straighten their fingers, they may reduce the amount of extension available at the wrist. Alternatively, tension in the finger extensors may restrict wrist flexion; for this reason a fully flexed wrist tends to exhibit straight fingers. We can tap into the tenodesis action during our yoga practice by allowing the fingers to passively move when we flex or extend the wrist. If we actively try to oppose these movements in the fingers, we will make the wrist movements much more difficult and will reduce the wrist’s range of motion.

For many yoga students, flattening the palms while in an arm balancing posture will decrease the amount of wrist extension available. Since it is hard enough for most students to balance on their hands or to extend their wrists to 90°, allowing the fingers to flex may provide that little extra range of motion they need to successfully perform the posture without any pain. Full wrist extension is the close-packed position for the wrist and the position of greatest stability.2 For this reason, whenever we are bearing weight on our hands, we instinctively keep the wrist extended. Look at photos of people doing hand balances and you will see almost all have their fingers curled.

Many Gymnasts Resort to Bending Fingers

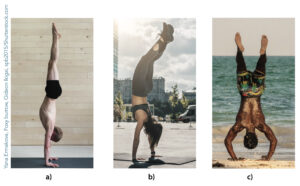

Gymnasts maintaining balance in handstands can employ four strategies: controlling movement at the hips, shoulders, elbows or wrists (see figure 3). Most employ a wrist strategy to control their center of gravity.3 To do so, they apply pressure from the fingers to the ground. Balancing movements will mostly occur at the wrists and shoulders, with very little happening at the elbows or hips.4 Only if the wrist strategy fails will the gymnast start to compensate at the elbows,5 which serves to lower the center of gravity and makes balancing easier but muscularly more demanding.6 This is similar to bending our knees if our standing balance is challenged. If the area of support is small (if the gymnast has very small hands or is balancing on a small platform, like a beam), a shoulder strategy may be chosen instead of an elbow strategy.7

This begs a question: what is a wrist strategy? It is the idea that we can most effectively control our center of gravity and keep it above the center of pressure in the hands by changing the forces in the fingers and palm, rather than changing the angles of other body parts. In an average handstand, about 75% of the weight of the body is borne in the palm, leaving the other 25% to fall into the fingers, but the exact amounts depend on the position of the hand and fingers.8 With a wrist strategy, balance is maintained by small movements at the wrists: if the body is falling too far forward, more flexion force at the wrist is applied. If we are too far back, more extension force is created.

Hands Flat or Fingers Tented?

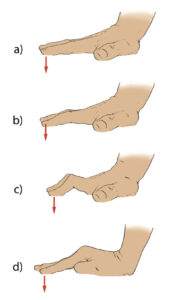

There is an ongoing debate in the gymnastics community over the optimal position of the hand and fingers during a handstand (see figure 4). Should hands and fingers be flattened (a) or curled (c) which is also called “tented”? This is an old discussion, and there are proponents on both sides with great rationales for their positions.9 On the one hand, spreading and flattening the palm and fingers increases the leverage the hand can provide, which makes maintaining balance much easier. The longer the levers, the less effort required.10 On the other hand, the hand and wrist are weaker when the fingers are flattened, and extension at the wrist may be reduced if the fingers are prevented from flexing.

Obviously, people with smaller hands relative to their overall body height and weight will have less leverage available to maintain their balance than people with relatively larger hands. For those with smaller hands, flattening and spreading the fingers may be optimal. For people with larger hands, tenting the fingers may provide better strength and control. It comes down to individual preferences. There are many excellent gymnasts and yogis who employ tented fingers, and many who are just as prolific at hand balancing and employ flat fingers.

Some teachers advise yogis to “grip the ground” to help with maintaining balance in handstands and other arm balancing postures. The intention is sound; we want to exert a strong force into the floor, but gripping will direct some force toward the center of the palm. It is more efficient to point the force directly into the floor. It is the downward force from the hands and fingers, not the inward force toward the middle of the hand, that increases leverage.11 However, the inward force may help to stiffen all the other muscles of the hand and wrist through co-contraction, thus helping stabilize the wrist. Again, which works best for you?

Pressing the full palm to the floor is easier if the student has a lot of pronation available. However, for students who cannot pronate their forearm sufficiently to root their palms into the floor, what are their options? One is to have the hands wider apart and rotated outward. Outward rotation may reduce the requirement for forearm pronation and increase wrist extension, which may allow more pressure to be directed at the 2nd and 3rd metacarpophalangeal joints (those are joints between the fingers and the palms). This hand position may also involve more external rotation and less abduction of the arm at the shoulder, which may be better for some students. However, there are trade-offs to consider. Hands wider apart may prevent the heads of the humerus from being stacked underneath the glenoid fossae of the scapulae, so some scapular adjustments may be required to maintain joint congruency. Plus, with hands pointing out to the side, there is less control over forward and backward swaying; the wrist strategy may involve managing radial and ulnar deviation, which is more challenging.12

For many students, no matter how hard they try, they will never be able to root the base of the first two knuckles into the ground. Their 2nd and 3rd metacarpophalangeal joints seem to float above the floor no matter what they do. This may be due to a lack of pronation available at the forearm, or to the relative curvatures of the transverse arches in their hands. Like a table with one leg shorter than the others, where it is not possible to get all four legs on the ground at the same time, some palms may never be completely flat on the floor. In these cases, there are some options.

Wedges used under the thumb side of the hands may provide more surface area for the palm to press down into. If wedges are not available, roll up the outer edge of the yoga mat and use that as a wedge. Another option is to simply accept the inevitable and allow the base of the 2nd and 3rd fingers to be off the floor, as in figure 4d. You can still firmly press downward into whatever is on the floor, including the pulp of each finger, the sides of the palm and thumb, and the wrist. One option that should be rejected is having the teacher step on the hands in an attempt to flatten them.13 (If you are prevented from flattening your palms to the floor due to the anatomical structure of your bones, breaking those bones is not a good idea!)

So, should you bend your fingers when your palms are on the floor? Yes! No! Maybe? It depends!

_______________________________

[1] See R.J. Strauch, M.P. Rosenwasser, and M.J. Behrman, “A Biomechanical Assessment of Ligaments Preventing Dorsoradial Subluxation of the Trapeziometacarpal Joint,” Journal of Hand Surgery 24.1 (1999): 198–9, doi:10.1053/ jhsu.1999.jjhsu9924a1le03.

[2] See Donald A. Neumann, Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, 3rd ed. (Maryland Heights, MO: 2017), 230.

[3] See Glen Blenkinsop, Matthew Pain, and Michael Hiley, “Balance Control Strategies during Perturbed and Unperturbed Balance in Standing and Handstand,” Royal Society Open Science 4 (2017): 161018, doi:10.1098/rsos.161018.

[4] Gymnasts produce considerable movement at the wrist (12.4°) and shoulders (5.6°) to control stability, but the elbows (1.2°) and hips (0.9°) do not move much at all. See G. Gauthier, R. Thouvarecq, and D. Chollet, “Visual and Postural Control of an Arbitrary Posture: The Handstand,” Journal of Sports Sciences 25 (2007): 1271–8.

[5] See Petr Hedbávný, J. Sklenaříková, D. Hupka, and Miriam Kalichová, “Balancing in Handstand on the Floor,” Science of Gymnastics Journal 5 (2013): 69–79.

[6] See M.R. Yaedon and G. Trwartha, “Control Strategy for a Hand Balance,” Motor Control 7 (2003): 411–30.

[7] See Gauthier et al., “Visual and Postural Control.”

[8] See Chris Gatti’s hand-balancing research at

https://www.chrisgatti.com/new-blog/2017/4/28/the-start-of-handbalancing-research-

[9] Opinions about the best strategies for balancing in handstand are not uniform. See Hedbávný et al., “Balancing in Handstand on the Floor.”

[10] For several analyses of the biomechanics of handstands by a professional gymnast and cirque performer, see Chris Gatti’s website: https://www.chrisgatti.com/handstand-teaching

[11] See Chris Gatti’s blog post “Finger Use in the Handstand” at

https://www.chrisgatti.com/blog/2020/4/3/finger-use-in-the-handstand

[12] See P. Kong, S.Y. Leung, and Y. Han, “Effect of Hand Placement Position on Press-to-Handstand Techniques and Stability,” paper presented at the 29th International Conference on Biomechanics in Sports (2011),

https://ojs.ub.uni-konstanz.de/cpa/article/view/4830

[13] I have personally seen this adjustment done in Ashtanga classes, and there is a photograph of B.K.S. Iyengar stepping on a student’s hands in his book, Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health, rev. ed. (New York: DK, 2013), 68. This adjustment is not recommended!